Dissecting my CPU: Control Flow, Speculative Execution, and Branch Prediction

- Introduction: How does a CPU decide what to run?

- Branch Prediction? In my CPU? It’s more likely than you think

- Does branch prediction make my code faster? A little experiment

- Analyzing the results with VTune

- Conclusion

Introduction: How does a CPU decide what to run?

I’ve been quite bothered recently that I can’t figure out what’s going on inside my CPU. My recent article about vectors and lists is one example of the many ways that code performance can be dependent on CPU behavior in very opaque ways.

This time, I was actually reading this very nice introduction to CUDA GPU programming when I noticed this passage:

The GPU is specialized for highly parallel computations and therefore designed such that more transistors are devoted to data processing rather than data caching and flow control.

Data caching is familiar to me from the vectors/lists debacle mentioned above. I’m a lot less familiar with flow control.

Essentially, CPUs can run lots of instructions, and they can even run a few instructions in parallel. However, deciding which instructions to run and in what order is very important. This is flow control, and it’s a hard problem. Lazy planning might mean wasted cycles where no computation happens, and thus your program runs slower.

Here’s some pseudocode we can use as a hypothetical:

1. A = 10

2. B = 20

3. C = A + B

4. IF C > 25 THEN

5. D = B * 2

6. ELSE

7. D = A / 2

8. ENDIF

9. E = D + 5

Here’s a few observations that your CPU might make when deciding how to run the instructions for this code:

- 1 and 2 can run simultaneously

- 3 depends on 1 and 2

- We could calculate 5 or 7 in advance, but we don’t know which one we will need until we evaluate 4

We’re going to focus on the last point, which is called branch prediction. The CPU makes a guess about how a conditional will evaluate, and then it schedules the instructions. If it guesses correctly, it gets a nice speedup. If it guesses wrong, then it wastes a few cycles on instructions it won’t use.

Branch Prediction? In my CPU? It’s more likely than you think

Branch prediction is a special kind of speculative execution focused on guessing how a conditional will behave.

Intel CPUs first introduced branch prediction in 1993. The earliest versions of Intel’s branch prediction used a Branch History Table to track previous outcomes of branches. They would use this to predict how it might evaluate next time.

If the CPU predicts that a branch will run, it can go ahead and start running the instructions within it using any spare compute. Best case scenario: you guessed right, and now you’re ahead of the game. Worst case scenario: you guessed wrong, and you spent some compute on instructions that you’ll throw away.

Modern branch prediction is a lot more complex, and I’m not really qualified to talk about it. It also seems to be something of a closely-guarded secret; I don’t think Intel publishes their branch prediction practices.

Does branch prediction make my code faster? A little experiment

So let’s see it. Up to this point, branch prediction is basically just a mythical creature. It lives inside your CPU and makes your programs faster, but it’s practically invisible.

Except that Intel has a nice tool called VTune that can give some clues about what’s happening inside your CPU.

Let’s jump into a tangible example. I wrote two C++ programs that have the same core logic. We will call them the Predictable Program and the Unpredictable Program.

In both programs, you initialize a vector with some values, and then you make a little loop over the vector and do something conditionally:

int size = 50000000;

std::vector<int> data(size);

//Initialize the values in your vector here

...

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

if (data[i] % 2 == 0) {

sum += data[i];

} else {

sum -= data[i];

}

}

std::cout << "Sum: " << sum << std::endl;

But the two programs differ by the contents of data. The Predictable Program just has neatly increasing values:

std::vector<int> data = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ...}

While the Unpredictable Program uses random values:

std::vector<int> data = {39892460, 41522524, 9026937, 4131624, 35780601, ...}

In practice, what does this mean? In the Predictable Program, the statement (data[i] % 2 == 0) will alternate between true and false every iteration during the loop. On the other hand, there’s no way to predict how the statement will evaluate in the Unpredictable Program.

This difference makes these programs a perfect test case for branch prediction. Can we verify that the Predictable Program will be faster due to better control flow?

Analyzing the results with VTune

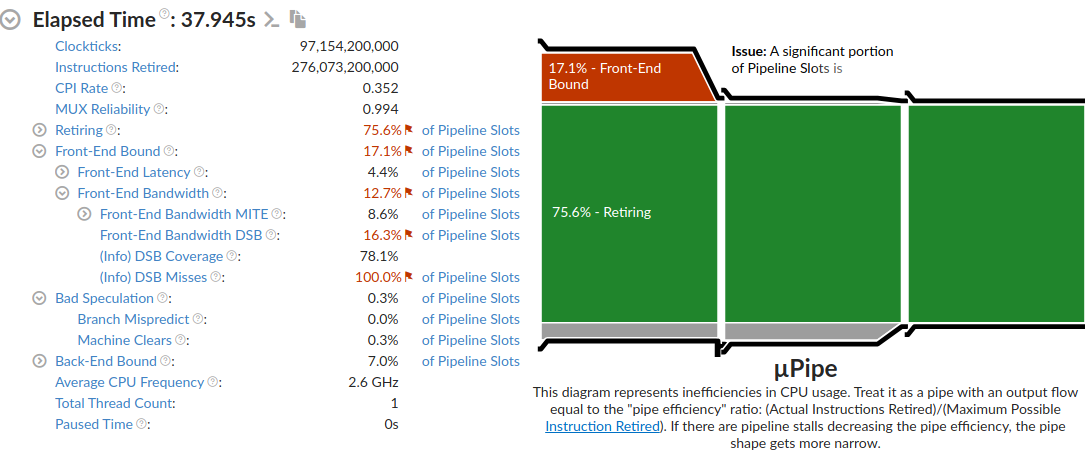

Predictable Program

VTune showed that this program was decently well-executed. The major issue was actually bandwidth constraints when initializing the vector with values from a file. I load the values this way so that both programs experience the same load from initialization.

The key point is that the good program experiences almost no branch mispredicts, which is good news!

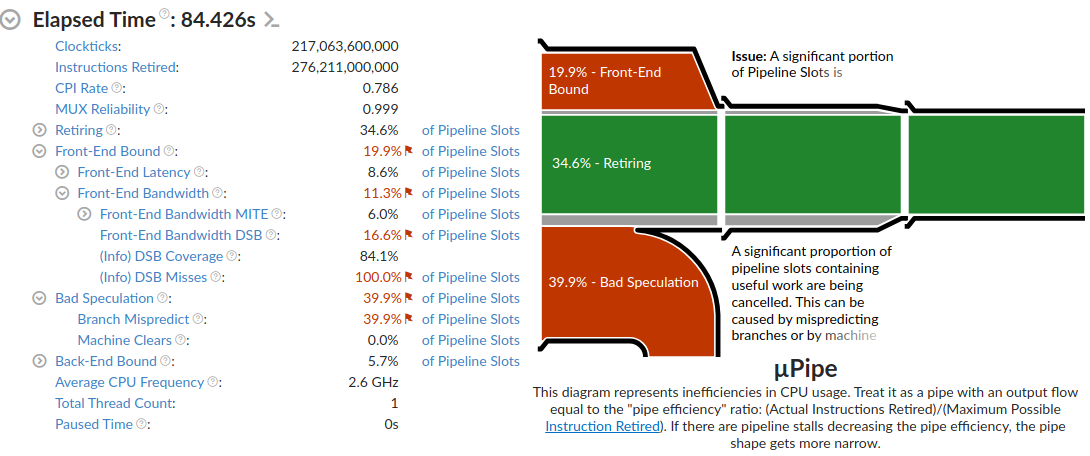

Unpredictable Program

The difference is quite visible here. Branch Mispredicts were a huge problem. They accounted for 39.9% of pipeline slots, loosely meaning (please fact check me on this) that we burned 39.9% of our operations on instructions that got thrown away.

That’s bad! This code is noticeably slower. In fact, timing just the core loop showed that the Unpredictable Program between 2x and 3x slower than the Predictable Program.

Conclusion

I don’t understand why CPUs are so opaque. They have all kinds of fancy tricks to make our code run faster, but then they don’t tell us! If you don’t know to take advantage, then you might end up writing code with lots of cache misses and unpredictable branches.

I’m learning that a hands-on approach to playing with CPUs has its benefits. Google search yields very little material of interest on these topics. ChatGPT was actually much more helpful to me when researching this project.

Anyways, if you know some textbooks or references that could help me learn more about how CPUs work, I’d be forever in your debt. Thanks for reading!