Contiguous memory matters: vectors vs lists in C++

- Big O complexity is (not) all you need

- Iterate and delete: a very simple script

- Differences between vectors and lists

- For our purposes, lists are theoretically better than vectors

- Surprise! Lists are not better, thanks to caching and contiguous memory

- Final reflections and conclusions

Big O complexity is (not) all you need

I’ve been doing a bit of LeetCode lately, which has gotten me in the habit of thinking about big O complexity. I had an occasion at work where I altered an algorithm to improve the its big O complexity. The coolest part was that my changes were extremely simple: just change a vector to a list!

And then I actually ran my new algorithm. The program still ran at the same speed, and was possibly slightly slower than before! What happened?!

The problem was that my analysis didn’t account for the computer architecture.

Iterate and delete: a very simple script

I stumbled upon some code that looked like this at work:

- Start with a big vector of things

- Iterate over the vector

- Delete a few of the things while iterating

We had a feeling this loop might be taking a lot of CPU time, and we needed to make it faster.

This sounds comically simple, but we can still ask ourselves: what’s the theoretical complexity of this procedure, and can it be optimized? There are basically two things to analyse: the cost of iterating over a vector, and the cost of deleting from a vector.

Differences between vectors and lists

A vector is really just a way to store an ordered set of things (integers, floats, structs, whatever) in memory. We can understand vectors better by comparing them to another standard data structure, lists. Vectors and lists achieve the same goal, but under the hood, they’re quite different.

Organization in memory

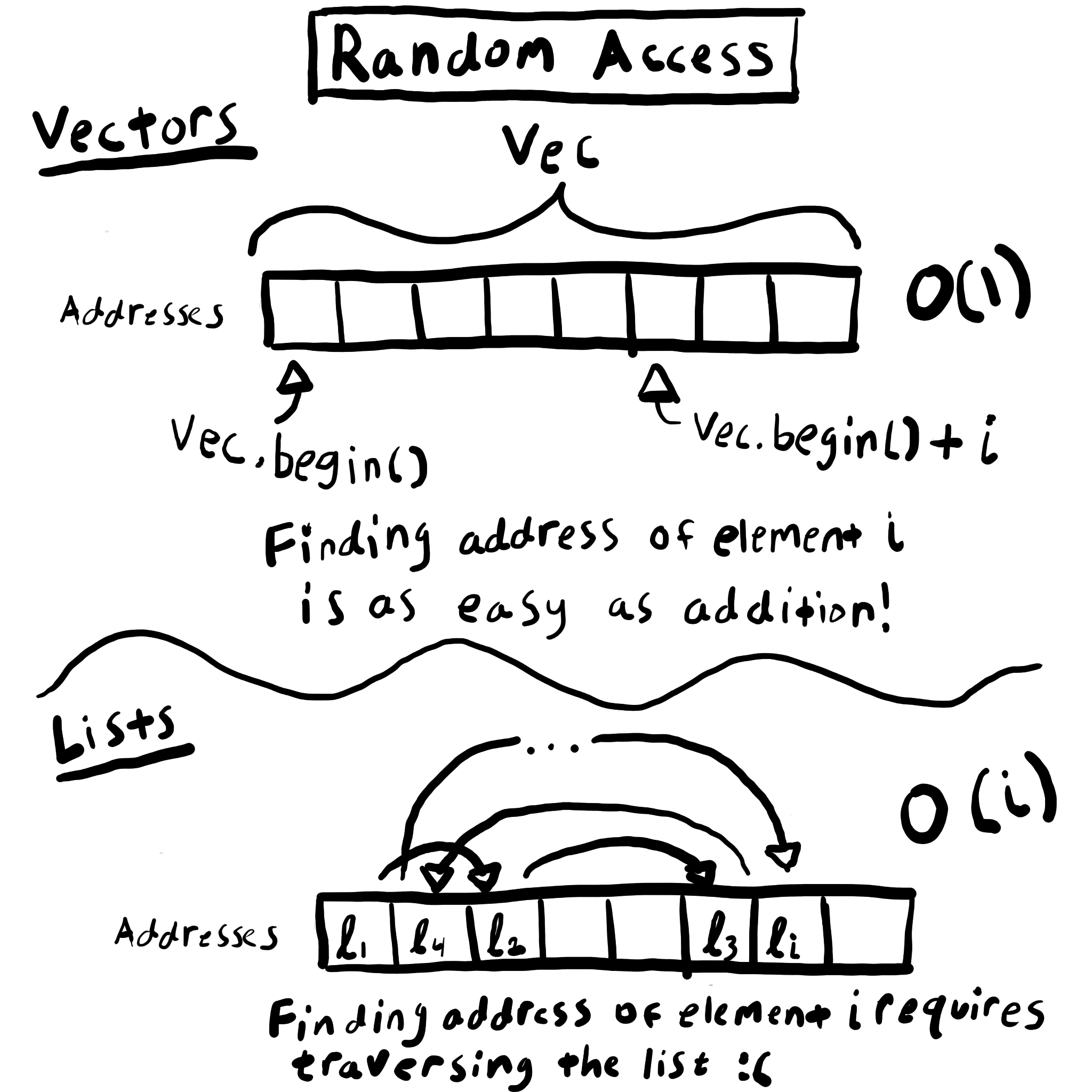

The most important property of a vector is that the allocated memory is contiguous. This means all the instances are stored next to each other (and properly ordered) in memory. As a result, it is easy to index particular elements of your set of things. If you know the memory address where the vector starts, you know exactly how to find element i: you offset the address by i.

Lists, on the other hand, don’t care about being contiguous at all. Every element of a list is stored with a pointer to the next element’s address. The memory can be anywhere and can be totally unordered.

Random access and iterating

The trade-offs between lists and vectors are due to the way their members are stored in memory. As you can see in the diagram, random access of any vector element is O(1) complexity. On the other hand, random access in a list requires iterating over the whole list, so it’s O(n) complexity with respect to the index being accessed.

However, this difference doesn’t matter for our script. We’re not doing random access; we’re iterating sequentially over all of the members. Iterating over a vector and iterating over a list are both O(n) (Can you see why?).

Insertion and deletion

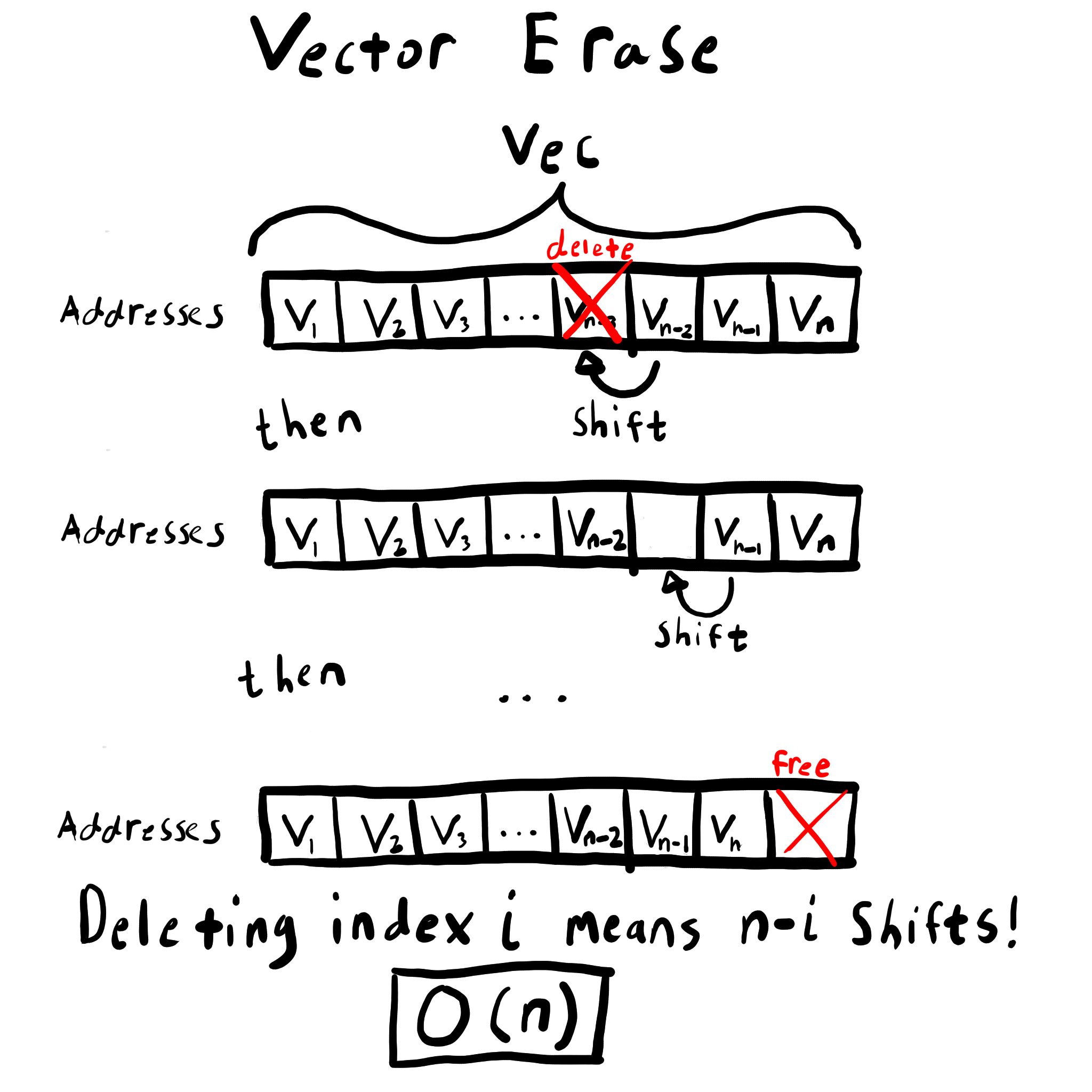

The complexity of these operations is also determined by the layout in memory of each data structure. Erasing an element from a vector is linear, i.e. O(n), with respect to the number of elements following the element to be deleted. This is because you have to shift the remaining members to keep the memory contiguous. Insertion is similarly O(n).

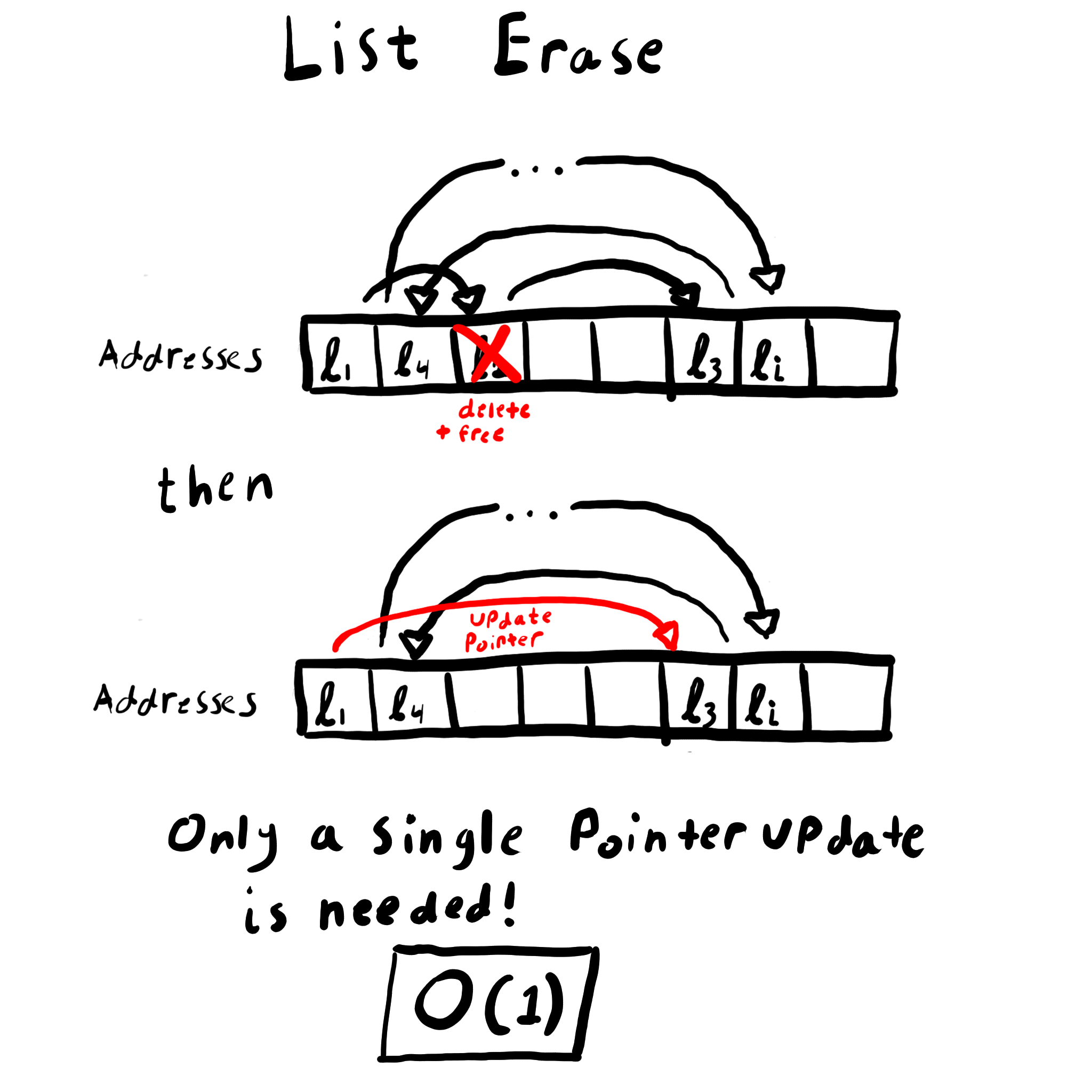

On the other hand, inserting or erasing from a list doesn’t require any reorganization of memory at all. The new elements can go anywhere, and we only need to update a single pointer in the list to finish an insertion. This makes list insertion and deletion O(1).

For our purposes, lists are theoretically better than vectors

So remember that our algorithm is basically just iterating over a set of objects and deleting a few of them. Let n be the number of objects and m be the number of deletions.

For a vector, iterating is O(n), and deleting is O(n). Since we do m deletions, the final complexity is about O(n + m*n) in the worst case.

On the other hand, traversing a list is O(n), but deletion is O(1). Then the complexity looks like O(n + m), which is nice and linear.

Surprise! Lists are not better, thanks to caching and contiguous memory

We tried swapping the vector for a list. Performance did not improve. Why not? Well, it turns out there’s more to life than big O complexity.

What is CPU cache, and what do we put in it?

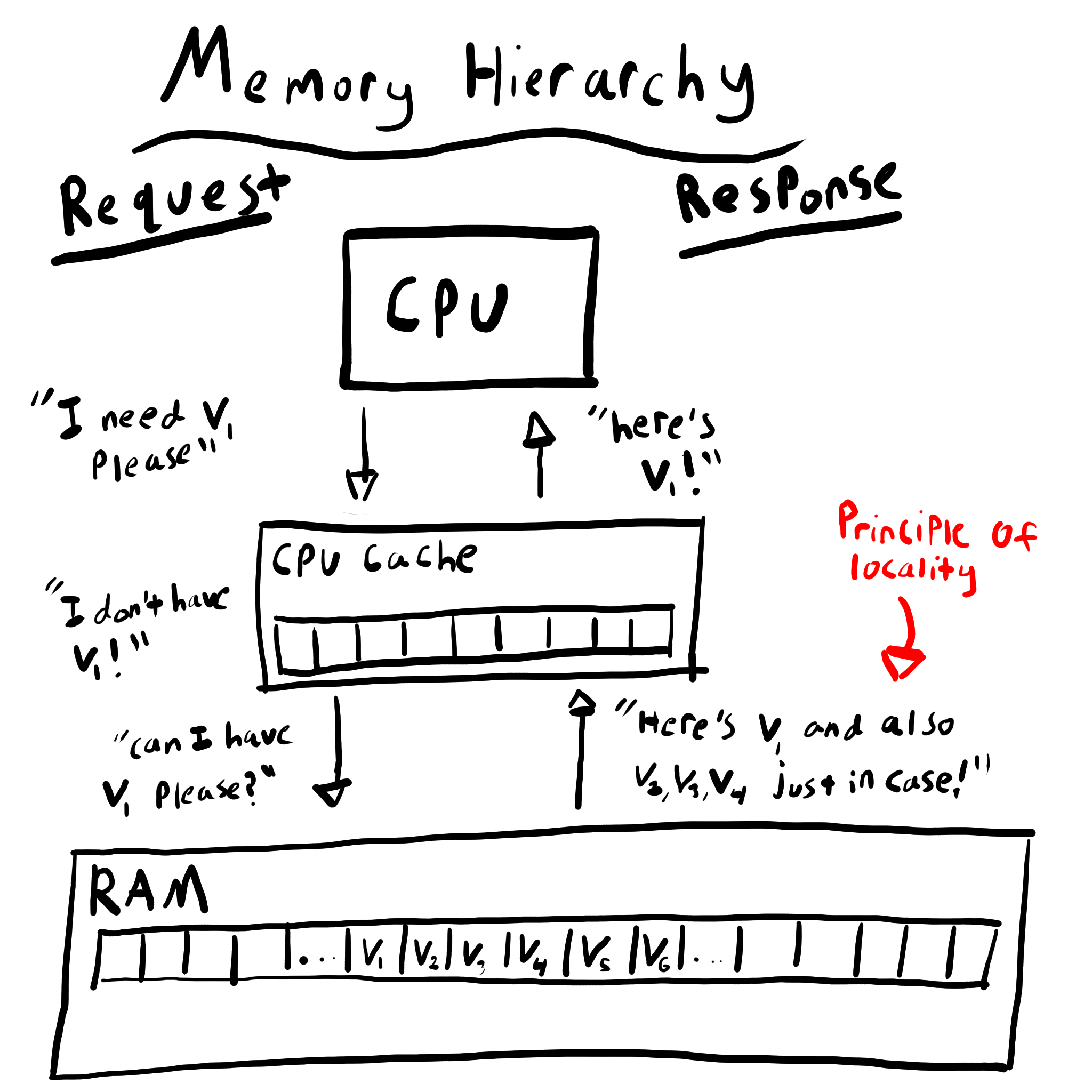

Accessing memory is slow, especially if you have to pull it from RAM. CPUs actually have a very small amount internal memory called the cache. Accessing memory from the cache can be an order of magnitude faster than pulling memory from RAM.

But the CPU cache is very small, so how do we decide what to put in it? In a perfect world, we could guess which memory the user will need, and then we’d load that memory into the CPU cache before they asked for it.

One of the assumptions used in computer design is the principle of locality. Essentially, if things are close together in memory, we can assume they’ll probably be accessed together. So, if you access an address that lives in RAM, the computer will load a chunk of nearby memory into the cache. That way, if you decide to access anything nearby, it will be much faster than pulling it from RAM!

Iterating over a vector is exactly the kind of operation that benefits from this clever use of the cache. The principle of locality works perfectly since we are accessing contiguous memory. Typically, the next item in the vector will already be in the cache when we need it. For long vectors, this saves us a lot of time that would otherwise be wasted pulling each member out of RAM.

On the other hand, since lists are stored willy nilly across memory, the principle of locality doesn’t help us at all while iterating. We end up having to pull a lot more of the list items out of DRAM, which wastes a lot of time.

So iterating over a list is slower than iterating over a vector

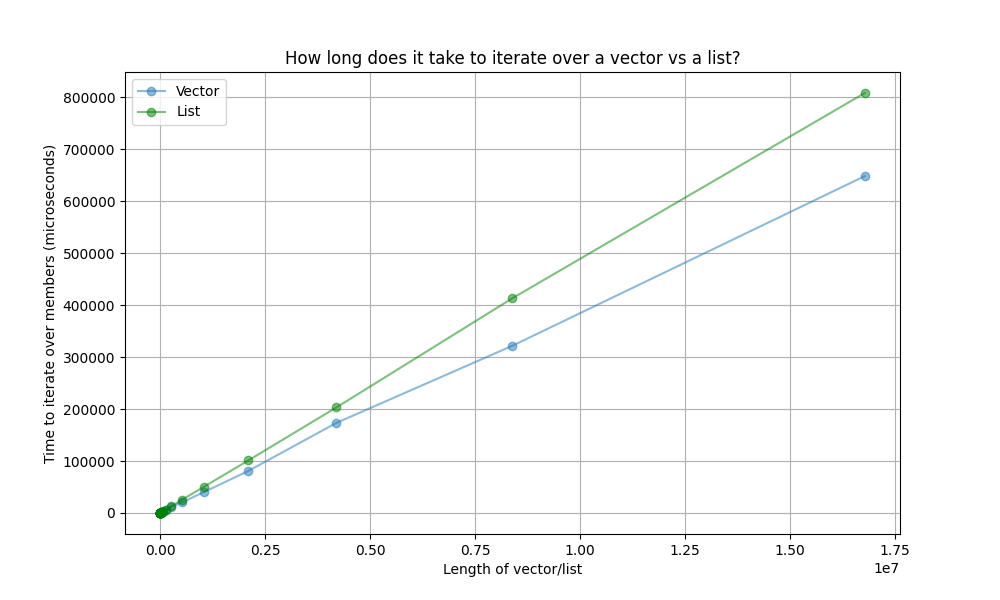

I did a comparison of iterating over vectors vs. a lists. No deletion here, just looped over the members and added a constant. The results show that vector is indeed faster at iterating:

Final reflections and conclusions

In our algorithm, we found that the slowdown in iteration outweighed the speedup in deletions. So, despite being better in terms of big O complexity, a vector was a better choice than a list.

Are you sure about all this? (No, I’m not)

No, not really. There’s a few things I still don’t understand. For one thing, cache misses should be an order of magnitude slower than retrieving from cache. Doesn’t that mean our list iteration should be, on average, an order of magnitude slower than vector iteration? The graph doesn’t seem to agree with this.

I also tried to profile the timing scripts with Intel’s VTune tool and see if I could observe the increase in cache misses. I could not; there seemed to be no change in cache misses between vectors and lists.

So lists are slower than vectors, but not nearly as slow as the theory would suggest. Where are the cache misses? And if the slowdown isn’t caused by cache misses, then what is causing it??

This seems to be a recurring theme with my excursion into computer architecture. I can identify symptoms, but they never fit the mental model. There’s always more nuance. I don’t even know how I’d proceed with investigating this problem further. If anyone has advice, please do let me know!