Pell’s Equation, Greek mathematics, and the square root of 2

- Introduction

- What is Pell’s Equation?

- Prehistory: solutions, but… no equations?

- (Optional) Explicit Greek computations with Pell’s equation

- $\sqrt{2}$ was a big problem for Greek geometry

- Pell’s equation approximates $\sqrt{2}$

- Theon of Smyrna’s side and diagonal method

- How I think Theon of Smyrna might have done it

- Conclusion: Shit is whack, yo

Introduction

This is Pell’s equation:

\[x^2 - Dy^2 = 1\]$D$ is a positive integer constant, and we want to solve for $x$ and $y$. Usually we want $x$ and $y$ to be whole numbers and greater than 0. You could probably find a solution for $D=2$ using pencil and paper.

Spoiler: one solution for D=2

$x=3, y=2$. Then $3^2 - 2*2^2 = 1$Recently I was trying to compute some integer solutions for Pell’s equation. After realizing my naive approach would not scale, I tried to derive something smarter. When that didn’t work, I turned to Wikipedia.

Pell’s equation does not look complex. And yet, despite its apparent simplicity, this equation occupied many of the world’s finest mathematicians for nearly 2000 years.

Learning about the historical development of Pell’s equation lets me experience second-hand how one can begin at something mundane and, through great labor, journey into the fantastic. Every hard-won fact about Pell’s equation is like a peek behind the curtain; we are glimpsing a thread of some transcendent tapestry which weaves together all things mathematical.

One of the most surprising facts I encountered about Pell’s equation was that it has a deep connection to approximating square roots. In fact, it was eventually discovered that calculating approximations to square roots is an efficient way to solve Pell’s equation. At first glance, this fact is unbelievable!

This article will discuss the early history of Pell’s equation and how the Greeks discovered the relationship between this equation and square root approximations, including my own conspiracy to explain how they derived some of their results

What is Pell’s Equation?

Pell’s equation is one example of a Diophantine equation. Diophantine equations are basically integer-valued equations where you’re only interested in integer-valued solutions. There are lots of different Diophantine equations that have interested mathematicians over the years.

Pell’s equation is expressed like so:

\[x^2 - Dy^2 = 1\]where $D$ is a positive integer.

That’s really all there is to it. It might feel painfully simple, but there’s a lot to be said about this equation and how to solve it.

Prehistory: solutions, but… no equations?

According to The Pell Equation by Edward Everett Whitford, architecture in ancient Egypt and Greece were often designed with ratios that happen to be solutions to Pell equations.

The ratio 17:12 is found many times on the Acropolis, and $x=17,y=12$ satisfies $x^2-2y^2 = 1$

Despite the appearance of the solutions, there is little evidence that these cultures were considering Pell’s equation at the time. This is partly due to the scarcity of preserved literature, particularly literature which regards mathematics.

However, the evidence we do have suggests Egyptian mathematicians were largely motivated by story problems, i.e. mathematics which described physical situations.

Already, history prevents a mystery to us. What drove these early cultures to derive solutions to Pell’s equation? And why would these values manifest in architecture?

The answer becomes more clear in the works of the Greek mathematicians.

(Optional) Explicit Greek computations with Pell’s equation

This section can be skipped. It shows that Pell’s equation in a “modern” algebraic form did occur in Greek mathematics. However, these examples are more like serendipitous encounters with Pell’s equation while investigating other problems.

I kind of think of these examples as “red herrings” in that they don’t really provide insight into Pell’s equation.

Archimedes

Although the Greeks didn’t use symbolic algebra as we do today, Pell’s equation was manifest in some of the problems studied by Greek mathematicians. Archimedes’s cattle problem was a complex mathematical riddle written around 250BC. Mathematicians of the late 1800s reformulated the problem as solving a particular Pell equation,

\[u^2 - (609)(7766)v^2 = 1\]where solutions for $(u, v)$ could be used to calculate the size of the number of cattle in the herd of the sun god (hint: it’s a lot of cattle).

As far as I can tell, it’s not known how (or if) Archimedes himself solved the riddle, so whether Archimedes actually engaged with Pell’s equation remains unknown.

Diophantus

Diophantus seems to have more directly encountered Pell’s equation. Page 22 of The Pell Equation by Edward Everett Whitford tipped me off to the location of a Pell equation in Diophantus’s Arithmetica.

In Book 5, problem 9, Diophantus solves the following problem:

To divide unity into two parts such that, if the same given number be added to either part, the result will be a square.

We will work through Diophantus’s solution up to the point that he solves a Pell equation.

Diophantus lets the given number be $6$, so that the objective is to find $x$ where $0 \leq x \leq 1$ (i.e. $x$ defines a division of unity) such that

\[x+6 = m^2 \: \text{ and } \: (1-x)+6=n^2\]You’ve probably noticed that Diophantus isn’t working with integers here. Indeed, Diophantus was generally interested in rational solutions rather than integer solutions, but later in this problem he will derive an integer-valued solution to a Pell equation anyways.

The first step is to observe that we can sum these two equations to derive a constraint:

\[x+6 + (1-x) + 6 = m^2 + n^2 \implies 13 = m^2 + n^2\]We can also note that $\vert m^2 - n^2 \vert = \vert x - (1-x)\vert = \vert 2x -1 \vert$, and therefore the difference between $m^2$ and $n^2$ must be less than or equal to 1.

With these constraints in mind, Diophantus sets out to solve $m^2$ and $n^2$.

First, he looks for a square that satisfies both of the constraints on $m$ and $n$. He does so by restating the problem: add a small fraction to $6\frac{1}{2}$ which will make it a square.

Diophantus guesses that the small faction to be added will have the form $\frac{1}{x^2}$. He also multiplies the problem by 4 to make it integer-valued. Apparently he sees this as inconsequential, probably since multiplying by 4 won’t affect whether a number is a perfect square. He lets this constant be absorbed by any squares in the equation. In other words, adding a small fraction to $6\frac{1}{2}$ to make it square is equivalent to solving:

\[26 + \frac{1}{p^2} = \text{a square}\]He multiplies by $p^2$ to get

\[26p^2 + 1 = \text{a square}\]Where, presumably, “a square” has consumed the $p^2$ term on the right.

Now we are looking at a Pell equation. If we let the square be $q^2$, then we can rearrange to

\[q^2 - 26p^2 = 1\]Diophantus seems to solve this intuitively by guessing that $q^2 = (5p + 1)^2$ so that

\[(5p+1)^2 - 26p^2 - 1 = 0 \implies 25p^2 + 10p + 1 - 26p^2 - 1 = 0 \implies 10p - p^2 = 0\]Which factors out nicely to give $p(10-p) = 0$. Thus $p=10$ solves the Diophantine equation, meaning $26 + \frac{1}{10^2}$ is square, and so is $6\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4*10^2}$, as desired.

There’s more to the solution of the original problem, but now you see how Diophantus stumbled upon a Pell equation and found a solution, essentially by guessing.

This representation of the problem is modernized, obviously. You can learn more about Diophantus’s original notation here.

$\sqrt{2}$ was a big problem for Greek geometry

Now we come to one of the most fascinating properties of Pell’s equation, which explains why it was of such great interest to several early cultures.

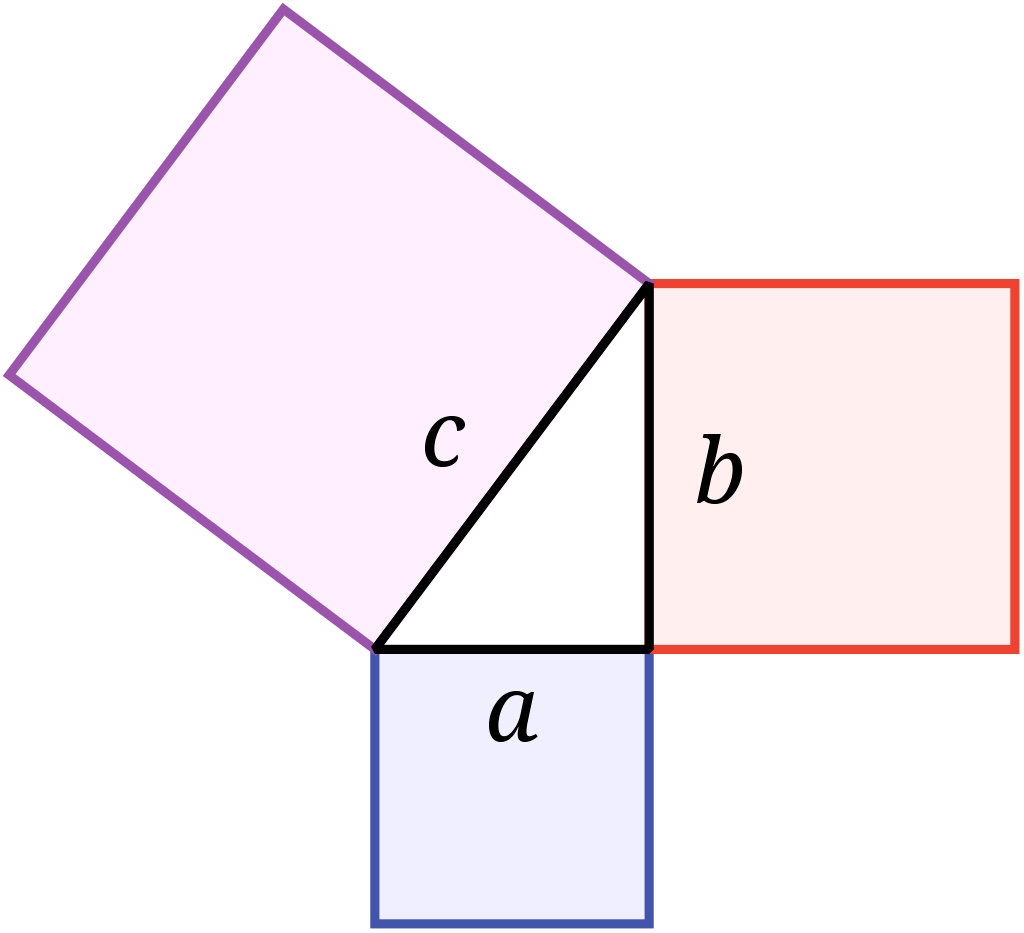

You may recall that the Pythagorean theorem for a right triangle with legs $a,b$ and hypotenuse $c$ states that

\[a^2 + b^2 = c^2\]Which you can visualize as a very literal comparison of squares built on the sides of a triangle (per Wikipedia):

Now consider an isosceles right triangle, meaning the legs have equal length. Then $a=b$, which means the Pythagorean theorem reduces to $c^2=2a^2$. But then the ratio comparing the side and the hypotenuse was

\[\frac{c}{a}=\sqrt{2}\]When the Greeks analyzed geometric figures, they often related lengths by constructing integer-valued ratios, “thrice this length is equal to twice that length” kinda stuff. They didn’t have a notion of decimals. There was only ratios, i.e. fractions using whole numbers to relate lengths to each other.

However, $\sqrt{2}$ has the unique property that it cannot be expressed as a fraction of integers. In other words, there is no $p,q\in\mathbb{z}$ such that $\frac{p}{q}=\sqrt{2}$. We say that $\sqrt{2}$ is an irrational number because of this. The Greeks would refer to such a number as “unspeakable.”

This may not seem like a big deal today. We can approximate $\sqrt{2}$ to many decimal places with a calculator. To the Greeks, the only way to surmount this problem was to find ratios $p/q$ which approximated $\sqrt{2}$.

These approximations were necessary. Often one would need good approximations of $\sqrt{2}$ for things like physical construction involving geometric blueprints.

Pell’s equation approximates $\sqrt{2}$

Consider once again an isosceles right triangle. Then $a=b$, so the Pythagorean theorem reduces to $c^2=2a^2$, and thus the ratio between side and hypotenuse is the unspeakable $\frac{c}{a}=\sqrt{2}$. In other words, there is no solution to the equation $c^2=2a^2$ where $c$ and $a$ are both positive integers.

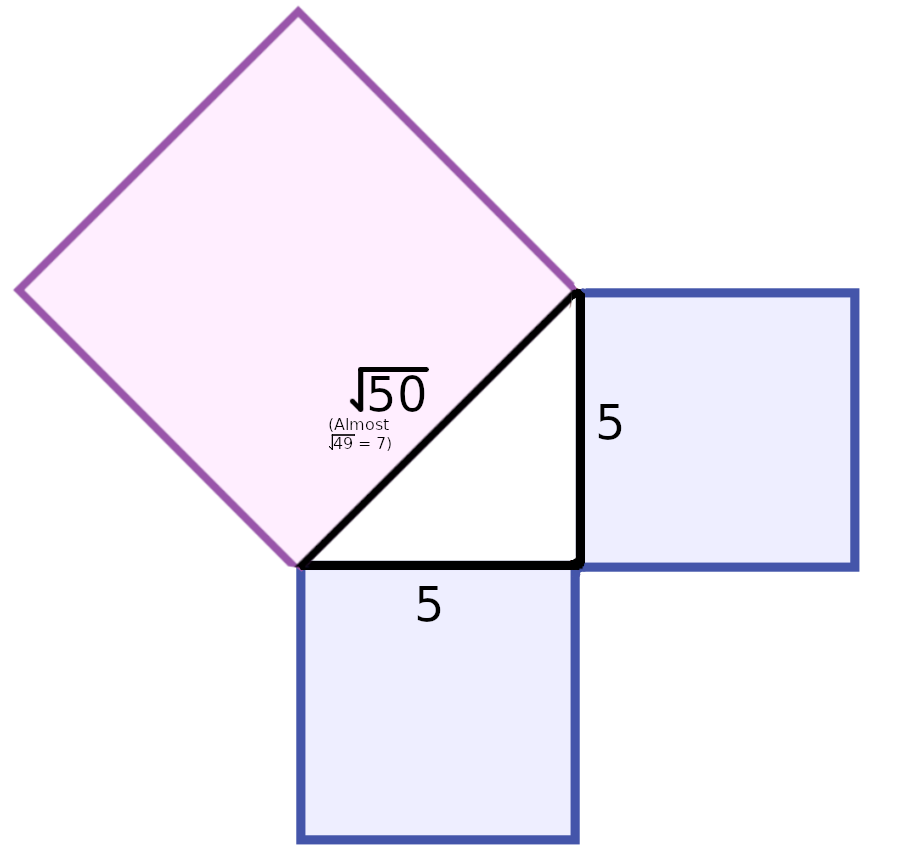

But sometimes these triangles are so close to being well-behaved! For example, if our sides have length 5, then $c^2 = 2*5^2 = 50$, so $c=\sqrt{50}$. This is still irrational, but it’s almost a perfect square, since $\sqrt{49}=7$. If only our hypotenuse had been one unit shorter, then the ratio between the side and hypotenuse would no longer be unspeakable.

Let’s continue this thought experiment. What if we relaxed the Pythagorean theorem just slightly, allowing for a little error? Say, for example, that

\[c^2=2a^2 + 1\text{,}\]Where the $1$ is our “error.” Now the lengths $c$ and $a$ don’t describe an isosceles right triangle, but we will see that they’re still a decent approximation of such a triangle if $c$ and $a$ are big.

In this case, we’d be looking for solutions where $c^2=2a^2 + 1$, or

\[c^2 -2a^2 = 1\]Which is Pell’s equation with $D=2$. Such solutions would satisfy

\[\frac{c}{a} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{a^2} + 2}\]Which confirms that when $c$ and $a$ are big, then you get a decent approximation of $\sqrt{2}$.

But are there integer solutions? Yes! There are actually infinitely many solutions for $(c,a)$. Here are the first few solutions:

| c | a | c/a |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | 1.5 |

| 17 | 12 | 1.4166 |

| 99 | 70 | 1.4142857 |

Considering that $\sqrt{2}\approxeq 1.41421356237$, these are not bad at all! Also note the appearance of 17 and 12. Now it becomes more clear why these values appeared in architecture. They were easily-measurable approximations of a right triangle!

The Greeks had observed all of this; they had noticed that some values $c,a$ could closely approximate a right isosceles triangle and yet $c/a$ was still speakable.

The utility of this fact was not lost on them, which provoked interest in generating values of $c,a$. Although they did not realize it, they were solving Pell’s equation for $D=2$!

Theon of Smyrna’s side and diagonal method

Theon of Smyrn’as side and diagonal method is one of the most well-known Greek techniques for approximating $\sqrt{2}$. It can be found in his book, Mathematics Useful for Understanding Plato, in the Arithmetic book at section XXX.

Once you have found a single solution to $c^2 -2a^2 = 1$, you can iteratively generate larger solutions using the side and diagonal method. As the values of $c$ and $a$ get larger, the approximation becomes more accurate.

I will start by presenting the method as Theon does. It begins as something of a thought experiment. We first explore the method using proper right triangles, where $c^2-2a^2=0$, and then we will discuss how it works for our approximations.

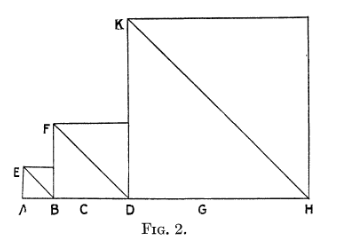

The Pell Equation by Edward Everett Whitford nicely illustrates the method like so:

We begin by constructing the smallest “square” using a known solution with side length $s_1=AB$ and diagonal length $d_1=EB$. To construct the next square, we “add the diagonal to the side, and to the diagonal let us add two sides…”

The first part, “add the diagonal to the side,” is straightforward. We construct BD so that BC is equal to AB, and CD is equal to EB. Then BD is the side plus the diagonal of the original square.

The second part, “To the diagonal let us add two sides,” is a little less obvious. First observe that $CD^2=2AB^2$. Then, we can use Euclid’s proposition X from Book 2 to conclude that

\[AD^2 + CD^2 = 2AB^2 + 2BD^2\]We can substitute $CD^2=2AB^2$ into this to get $AD^2=2BD^2$.

By the Pythagorean theorem, the diagonal $DF$ satisfies $DF^2 = BD^2$. Composing this with the above, we see that

\[DF^2 = AD^2 = (2AB + BD)^2\]and thus

\[DF = 2AB + BD\]So the diagonal of our new square is the original diagonal plus twice the original side.

In other words,

\[s_2 = s_1 + d_1 \text{ and } d_2 = 2s_1 + d_1\]We can repeat this endlessly to construct $s_n, d_n$.

So why have we done this at all? It’s just a way to construct bigger squares from smaller squares, right? But this method is special because it still works when we apply it to our “crooked” squares, where $c^2 -2a^2 = 1$.

We can start with our first crooked square with $s_1=2$ and $d_1=3$. Then if we apply the side and diagonal method, we get

\[s_2 = 2 + 3 = 5 \text{ and } d_2 = 2\*2 + 3 = 7\]But $7^2 - 2*5^2 = -1$, which means we still have an error of one, although now it’s negative. In fact, you can keep calculating new values, and you’ll find that the error is always one, and it alternates between positive and negative:

| $n$ | $s_n$ | $d_n$ | $d_n^2 - 2s_n^2$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 7 | -1 |

| 3 | 12 | 17 | 1 |

This pattern repeats indefinitely. As the squares get larger, the error stays the same, and every other square yields a solution to Pell’s equation!

Why does this method work for crooked squares? Why does the error stay small and alternate its sign? Well, we can verify that it works algebraically.

Suppose we know that $d_1^2 - 2s_1^2 = 1$. Then

\[d_2^2 - 2s_2^2 = (2s_1 + d_1)^2 - 2(s_1 + d_1)^2 = (4s_1^2 + 4s_1d_1 + d_1^2) - 2(s_1^2 + 2s_1d_1 + d_1^2) = -1(d_1^2 - 2s_1^2)\]But how in the world did Theon of Smyrna figure this out? We can see that it works, but it’s not at all intuitive. How would one ever construct a method like this from scratch?

How I think Theon of Smyrna might have done it

I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how one might stumble upon this method for generating solutions to Pell’s equation. Eventually, I found a natural investigation that might lead one to such a discovery.

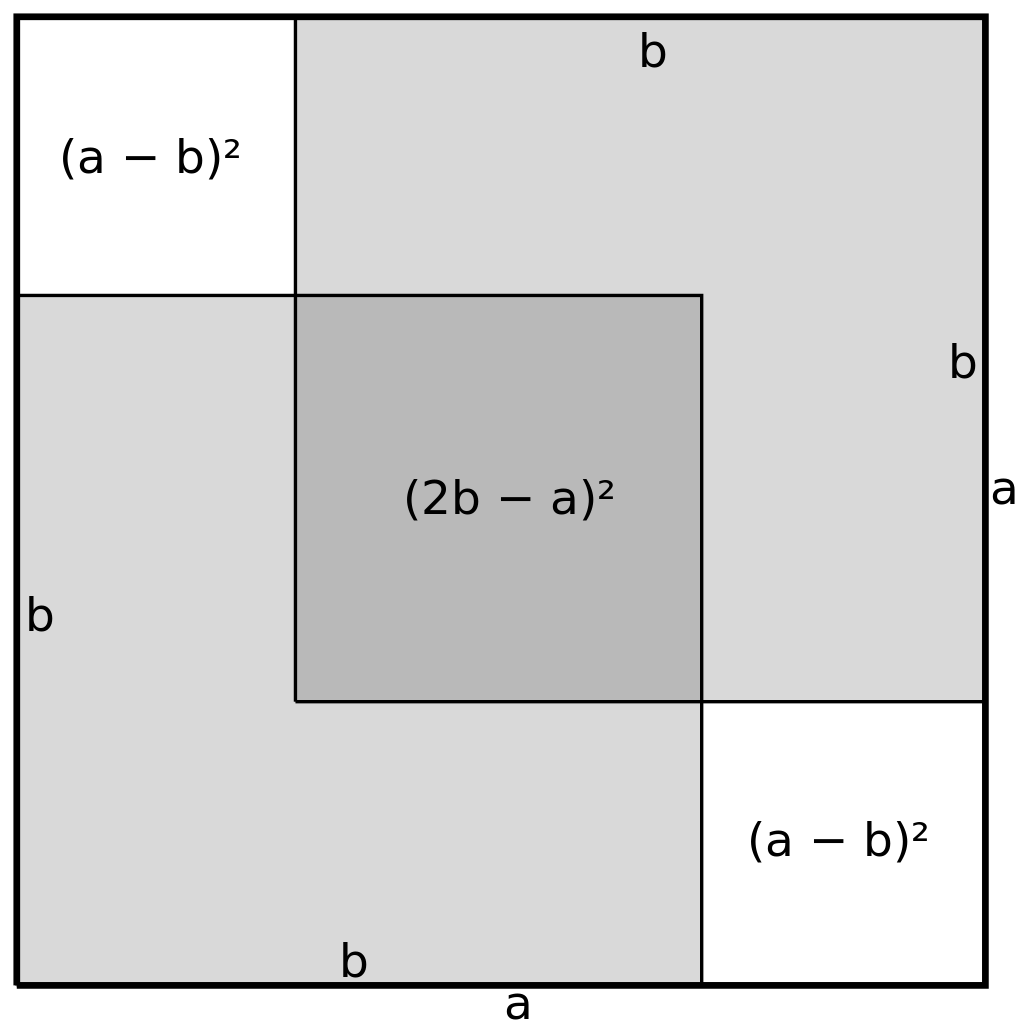

It started when I was looking at a proof by Stanley Tennenbaum that the square root of 2 is irrational. This proof was created in the 1950s, but it is quite beautiful in its brevity. We don’t need the details of the proof, though. What we really need is this illustration:

We begin with two squares with lengths $a$ and $b$, where one square has twice the area of the other. In other words, $a^2 - 2b^2 = 0$. The picture shows two copies of the smaller square placed inside the larger square.

Logically, we can compare the small middle square with the two outer squares to conclude that

\[(2b-a)^2 = 2(a-b)^2\]Another interesting property is that these smaller squares both have integer-valued sides. By repeating this argument indefinitely, we can get a contradiction to conclude that $\sqrt{2}$ is not rational.

However, now let’s consider the same image, except we assume that

\[a^2 - 2b^2 = 1\]Which is to say we assume the larger square has twice the area of the smaller square plus one more unit of area. This is equivalent to saying that $a$ and $b$ solve Pell’s equation.

Then similar to last time, we can conclude that

\[(2b-a)^2 + 1 = 2(a-b)^2\]But as before, the values $2b-a$ and $a-b$ are still integer-valued, and they’re nearly a solution of Pell’s equation, except the sign of the 1 has flipped. Is this sounding familiar?

Essentially, this geometric investigation leads one to discover the reverse of the side and diagonal method. From larger solutions of Pell’s equation, we can generate smaller solutions!

It’s not hard to see that this process is reversible, and the reverse is exactly equivalent to the side and diagonal method.

My hunch is that Greek mathematicians were far more likely to discover this relationship first, which then led them to reverse the process and construct larger solutions in order to get better approximations of $\sqrt{2}$. This is just my own personal conspiracy, and I have no evidence except that it makes a lot of sense to me.

Conclusion: Shit is whack, yo

This project got way out of hand. To be honest, I was just trying to solve a Project Euler problem. I wanted to understand the solution thoroughly before implementing it, but it turned out to be a pretty big job. I got a little obsessed with creating a narrative motivating the study of Pell’s equation, and then I wanted to figure out how I might have done things if I were from Smyrna.

There is a lot of other cool information about Pell’s equation that I didn’t have time to touch on here. The Chakravala method and Brahmagupta’s identity are both fascinating. I’m also curious about the general theory of Pell’s equation formulated by Lagrange in 1766.

This has also instilled in me a new sense of respect for binary quadratic forms. In my undergrad I read a lot of Cox’s book, Primes of the form x^2 + ny^2, which was interesting, but I didn’t have much perspective on number theory at the time. In a way, the theory of binary quadratic forms is a broad generalization of the study of Pell’s equation, which is mind-boggling to consider. I think this all paves the way for class field theory, which is a whole ‘nother can of worms.

Anyways, I hope you enjoyed this. My blog analytics showed me that essentially no one reads my math posts, and those who do have an average engagement time under 30 seconds. But hey, at least you had the decency to skim the conclusion. I appreciate that, seriously. I take what I can get.