Egyptians and the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: Historical Context (1)

Preface

Recently I had the idea that I might appreciate mathematics more if I understood how it originated. “I’m so clever,” I thought, “I’ll just Google ‘Ancient Egyptian Mathematics’ and then everything will make sense.” Surprise! Nobody has a complete understanding of Egyptian mathematics. There are many mysteries about how Egyptians performed mathematical operations and how Egyptians understood mathematics.

To make matters worse, I’m beginning to suspect that there’s not a simple solution. I’m not going to have a breakthrough and think “Oh, that’s what mathematics meant to Egyptians!” The deeper I dig, the more mysteries present themselves…

As such, this series of blog posts is an attempt to document my experience of digging ever deeper in search of answers which don’t exist.

I’ll warn you now; this first post is going reference Wikipedia. Deal with it.

Intro

We start with a very brief history of Egypt from its origin up to the point at which the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus was written. Next we describe the RMP and discuss simple observations about the problems it contained.

Egypt: A Timeline Up To The RMP

Set the scene in Egypt, circa 3500 BC, along the Nile. It was well over 5000 years ago. Large cultures along the Nile have been practicing agriculture and animal husbandry, making pottery, and generally having a good time. There were stone, copper, and obsidians tools, there was jewelry and painted ceramics, and there was an ongoing consolidation of power around the Nile valley.

In passing, note that the earliest known Hieroglyphic writing appeared suddenly in 3250BC, already a complete writing system. Its origins are unknown.3

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Map_of_Egypt-f1a95b7e0515423aaa66bad08b627d50.jpg) |

|---|

| A map of ancient Egypt2 |

We will boldly proclaim the beginning of Egyptian civilization to be placed around 3000BC, in what is called the Early Dynastic Period. At this point, power in Egyptian society began to consolidate under Dynastic kings. There were more elaborately constructed tombs and government institutions.

Around 2686BC, things really started to take off during the Old Kingdom period of Egypt. “Major advances in architecture, art, and technology were made during the Old Kingdom, fueled by the increased agricultural productivity and resulting population, made possible by a well-developed central administration.”1 Shit like the Giza pyramids and Great Sphinx happened next. There were large, coordinated government operations involving collecting taxes (mathematics is important for taxes).

|

|---|

| A timeline, as promised1 |

Next there was government collapse, food shortages, re-emergence of organized societies, more kings, innovation in the arts, kingdoms weakening, introduction of the composite bow (by the invading Hyksos), war campaigns, and eventually (surprisingly) prosperity by the time you reach 1500BC.1 It was a busy era.

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus

This happens to be around the time that the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (RMP) was written. The RMP is basically a huge scroll detailing many mathematical problems and solutions. Its design suggests that it was intended to be used by a teacher to assign problems to students.3 It was written near 1550BC.

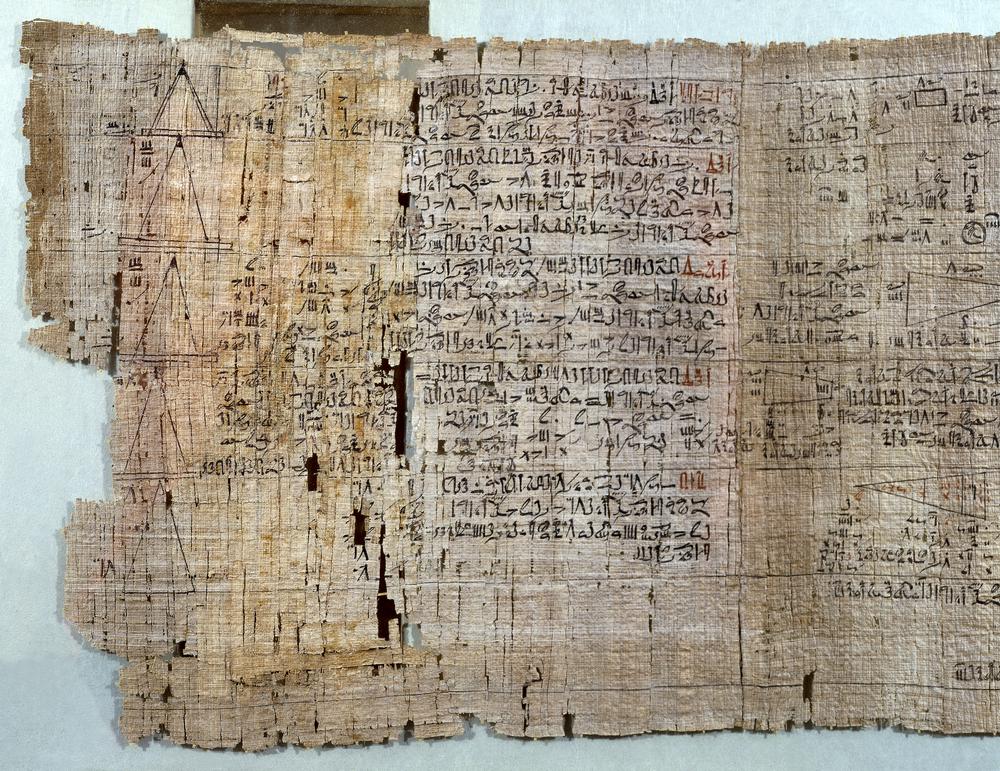

|

|---|

| A sample of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus |

The original RMP is lost. The available copy that exists today claims to be written by a scribe named Ahmes approximately 200 years after the original RMP was written. The scroll itself is about 13 inches tall and would have been 13 ft long altogether.

The RMP is one of the major bodies of evidence about ancient Egyptian math and how it related to Egyptian society. It contains “a series of general mathematical problems, which are nevertheless concrete and representative of the practical day-to-day situations that were expected of the graduating apprentice.”9

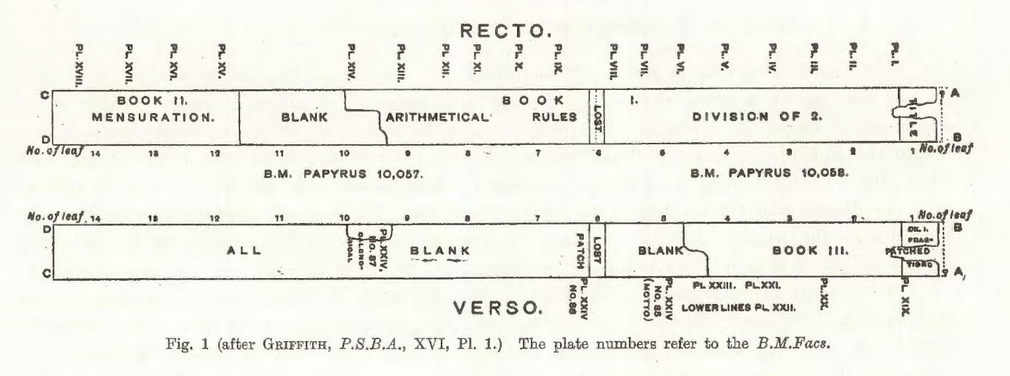

Scholars generally agree that the scroll is divided into three parts, which we refer to as “Book 1: Arithmetic,” “Book 2: Geometry,” and “Book 3: Miscellaneous.”3 These, in turn, are divided into ordered problems, which we typically refer to by number. For example, problem 39 is in Book 1 and concerns distributing 100 bread loaves among 10 men unequally according to some algebraic rules.

|

|---|

| A roadmap of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus8 |

We will finish this article by hinting at the flavor of the three books.

Book I: Arithmetic

This is basically the “bread-sharing” part of the book. Many of the problems describe dividing up bread to share among men in different ways. However, there are also mathematical problems which offer no concrete context. One of which solves a linear equation. Many of the others regard the use of “Egyptian fractions,” which involved determining and proving identities such as

\[\frac{4}{10}=\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{15}\]Egyptian fractions will be discussed further in future articles. Their nature is still not totally understood, and frankly, I think it is very interesting.

Book II: Geometry

The problems in Book II were about measurement of length, area, and volume. They also measured slope (degree of flatness) and “lack of quality indicating a dilution factor in such commodities as bread and beer.”4

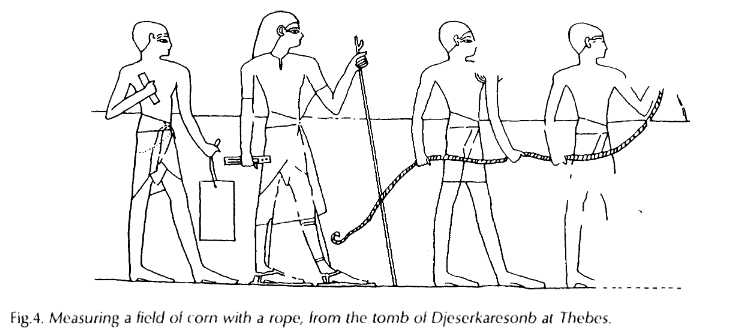

All of these measurements have convenient practical motivations. Area, for example, was used in taxation.5 A government agent, the “holder of the cord,” would measure the area of property where grain was grown, and the property owner would be taxed a percentage of their total crop.

|

|---|

| Taxation goes way back4 |

Volume was commonly used for measuring grain or flower as well as liquids such as beer. For example, RMP section 42 computes the volume of a circular granary in terms of barrels.6 This kind of math would be useful for knowing how much grain your kingdom possesses and preventing famines and governmental collapse.

Book III: Miscellaneous

Book III is full of miscellaneous problems. No grand narrative that I can weave off the top of my head. There’s more Egyptian fraction problems, some vaguely humorous problems, and a lot of other stuff. Here’s an example problem:

A bag of three precious metals, gold, silver and lead, has been purchased for 84 sha’ty, which is a monetary unit. All three substances weigh the same, and a deben is a unit of weight. 1 deben of gold costs 12 sha’ty, 1 deben of silver costs 6 sha’ty, and 1 deben of lead costs 3 sha’ty. Find the common weight W of any of the three metals in the bag.4

Conclusion

Egypt had a lot going on. Their civilization is so ancient that it is difficult to retrieve and interpret their artifacts. However, what we have discovered has given us many insights into what the life of an Egyptian may have been like. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus is one of these windows into the past. What can we learn from it? Follow me on Twitter to find out.