Egyptians and the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: Egyptian Arithmetic (2)

- Intro

- Hieroglyphic

- Egyptian Numerals

- Adding And Multiplying

- Division and Egyptian Fractions

- Conclusion

Intro

If you’ve read the first article in this series, then you may be aware of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. The RMP is an Egyptian scroll and one of the earliest written mathematical documents. Rather than diving straight into the RMP, this article discusses the written Egyptian language, hieroglyphic, as well as the Egyptian number system and basic Egyptian arithmetic.

Arithmetic may sound like trivial material to some, but the Egyptians did not have the intellectual infrastructure we take for granted today. The Egyptian methods and notation we will discuss are over 3000 years old and were practically the first written mathematics in Egypt. They are a far cry from modern algebra.

Hieroglyphic

You don’t really need to know about hieroglyphs to understand Egyptian numbers, but I’m going to tell you about it anyways.

This section is a criminally-reductive paraphrasing of “Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs” by James P. Allen.

The first known Egyptian writing is dated around 3200BC, near the beginning of Egypt. The language survived until around 1100AD, and it has many distinct stages of life. The stage which interests us most is Middle Egyptian (2100BC-1600BC). Middle Egyptian is one of the best-understood eras of Hieroglyphic. The RMP was written in Middle Egyptian.

Middle Egyptian was composed of around 500 unique hieroglyphs. Each hieroglyph was an illustration. Every hieroglyph could be used in each of three ways:

- As an ideogram, meaning that the hieroglyph means what it depicts. For example, a hieroglyph depicting a house, if it is used as an ideogram, is supposed to convey the concept of a house.

-

As a phonogram, meaning that the hieroglyph is supposed to convey the sound of pronouncing the word associated with the hieroglyph’s ideogram. For example, we can communicate the word “belief” by using the following pictures as phonograms:

Using phonograms to communicate spoken words in writing - As a determinative, meaning that it indicates whether other hieroglyphs should be read as ideograms or phonograms. Words were made by groupings of hieroglyphs ending with a determinative that instructed you how to read them.

|

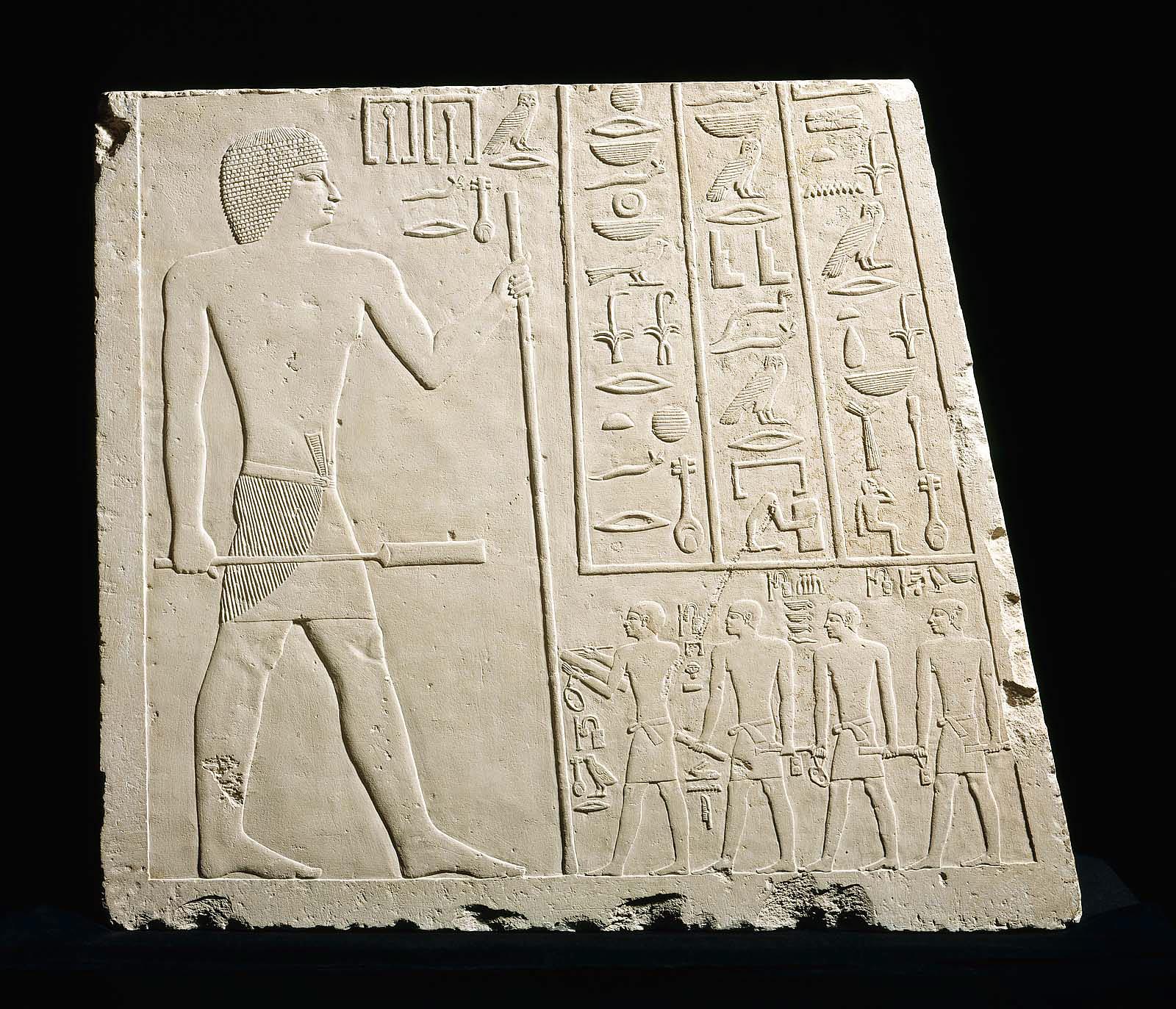

|---|

| Hieroglyphs on the Relief of Nofer from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts |

There’s, like, a lot more to understanding hieroglyphic, but these three concepts outline the basic functionality.

The Egyptians also wrote in hieratic, which was essentially the cursive version of Hieroglyph. Hieratic was more common for scrolls and bureaucratic texts, while hieroglyphic would be used for rituals and decoration in tombs and palaces.

|

|---|

| Hieratic writing, “Be on your guard against all who are subordinate to you… Trust no brother, know no friend, make no intimates.”6 Probably lyrics by an Egyptian rapper or something |

Egyptian Numerals

Before written language, it is commonly believed counting was performed through the use of tally marks.

Carving notches into bones is the earliest concrete evidence of counting, possibly going as far back as 30,000BC.3 There is usually debate surrounding any example of tally marks in the pre-language era, something like, “you don’t really know they were counting! They could have just been goofing around!” Sure, whatever.

|

|---|

| Counting?3 |

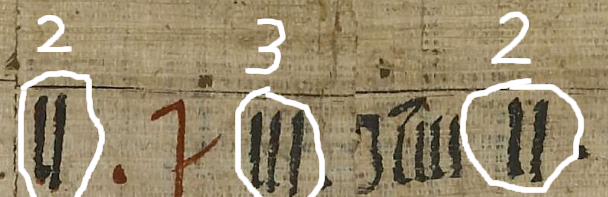

It should come as no surprise, then, that the Egyptian symbol for 1 appears to be simply a tally mark, and for small numbers, they just wrote more tally marks.

|

|---|

| Egyptian hieratic depiction of the numbers 2 and 3 from the RMP |

Tally marks quickly became inconvenient for larger numbers, so new symbols were created to represent these numbers. Coincidentally, the Egyptians used a base 10 numeral system. Perhaps there is some relationship to counting on fingers?

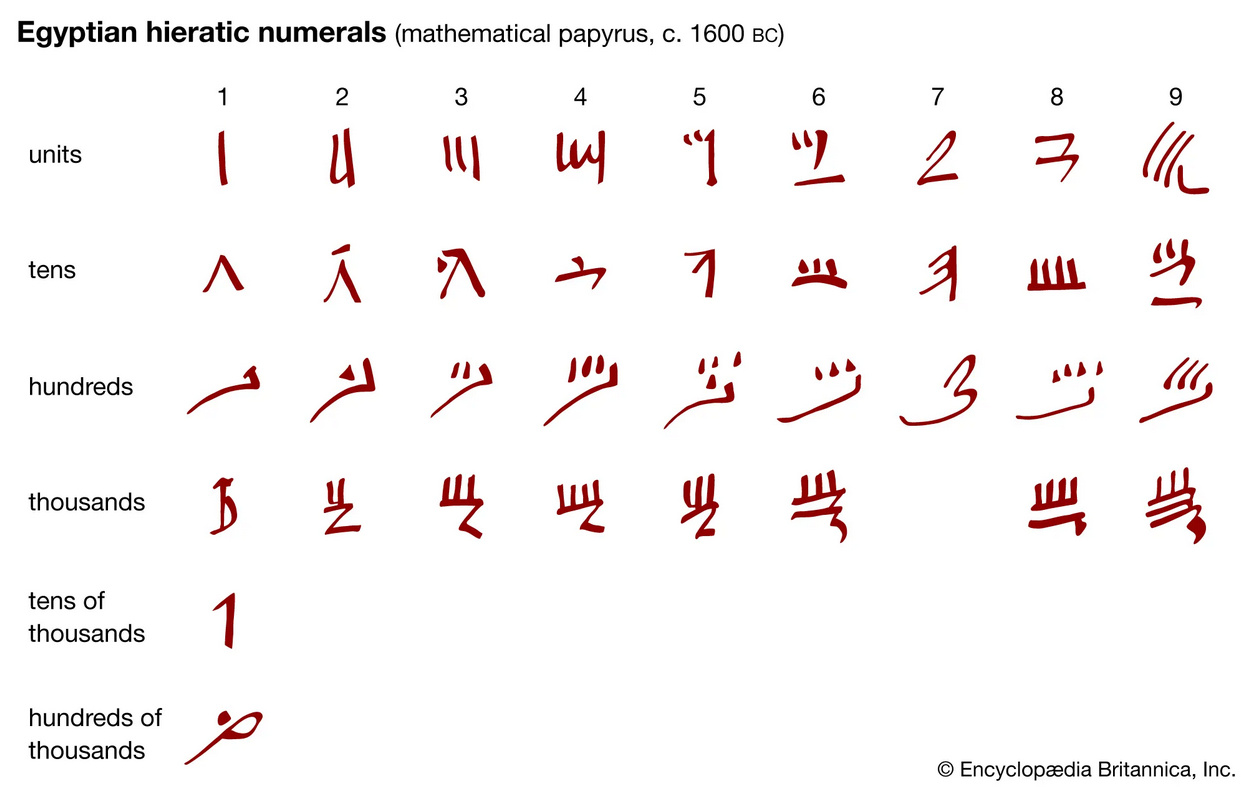

|

|---|

| Behold, numbers4 |

Numbers were represented as groupings of these symbols. A number is equal to the sum of its substituent hieroglyphics.5

For example, here is the number 17 depicted in the RMP:

|

|---|

| The number 17 |

Warning: The Egyptians didn’t give a fuck, and they apparently invented multiple symbols to represent the same numbers. For example, the RMP often depicts 4 as a single horizontal bar (half of an 8, if you will). I haven’t found any scholarly sources discussing this. We all just have to live with it.

Adding And Multiplying

Egyptians were fairly comfortable with arithmetic, i.e. adding, multiplying, and dividing. They had somewhat standardized procedures for these operations. They did not use algebraic symbols like our $+$ and $*$ signs, so specifying the operation to be performed was done in words or intuited from the context.

Adding two numbers was pretty simple to the Egyptians. You literally put them together, and if you’re feeling really generous, you can reduce it to make it prettier.

Egyptian multiplication was a little more complex. Using modern algebra, you can think of it like this:

Say you want to calculate $33*47$.7 Calculating this directly might be annoying, so the Egyptians would break it up into easier products:

\[33*47 = (1 + 10 + 20 + 2)*47 =\] \[1*47\] \[+10*47\] \[+20*47\] \[+2*47\]If the Egyptians didn’t know how they wanted to break apart a number, they would use the base 2 decomposition:

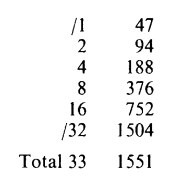

|

|---|

| Multiplication using powers of two7 |

Scholars generally regard this as “absolutely nuts,” because it’s crazy that the Egyptians figured out every number can be represented as a sum of powers of two. Some sources suggest this method of multiplication by doubling may have originated from Africa.5

This idea of breaking apart a number into a convenient sum is huge in Egyptian mathematics. It was also commonly applied to division.

Division and Egyptian Fractions

Fractions

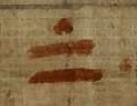

Okay, this is where shit starts to get really weird. First, let’s talk about fractions. In hieratic, any number $n$ could be modified by putting a dot above it in order to represent $\frac{1}{n}$.

|

|---|

| The fraction 1/8 |

In proper Egyptian Hieroglyphic, the eye symbol er was used instead of a dot. er can mean “from” or “of,” perhaps intending to convey  as “(one) of 3.”

as “(one) of 3.”

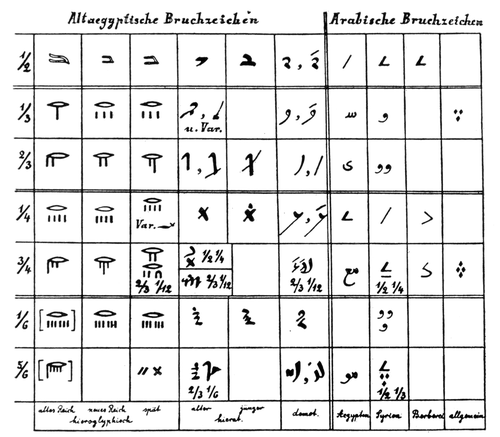

There were also, of course, special symbols for certain common fractions:

|

|---|

| Table of common fraction symbols.8 |

The way that Egyptians used these fractions was weird. They preferred not to repeat fractions. Depicting $\frac{2}{5}$ as

was considered “unfinished.” One was expected to instead calculate (or look up) a sum of unique unit fractions equal to $\frac{2}{5}$.

was considered “unfinished.” One was expected to instead calculate (or look up) a sum of unique unit fractions equal to $\frac{2}{5}$.

|

|---|

| The 2nd row of the RMP’s 2/n table calculates $\frac{2}{5}=\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{15}$ |

In fact, the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus begins with a massive table called the “2/n table” which calculates a unique sum of unit fractions for $\frac{2}{n}$ starting with $n=3$ and going all the way to $n=101$! That’s bonkers.

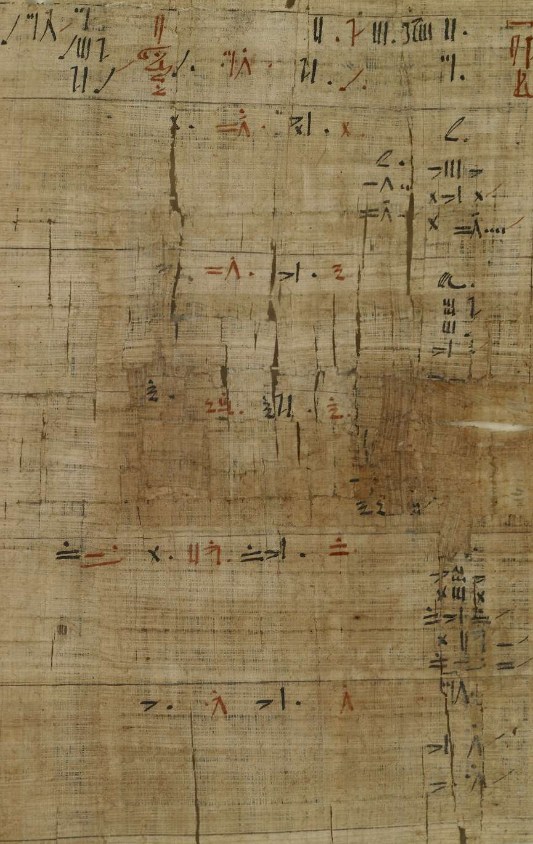

|

|---|

| The first column of the 2/n table covering n=3 through n=15. The $n$ value for each row appears on the right-hand side. Values in red denote the sums of unit fractions. |

It’s not clear why the Egyptians felt the need to represent vulgar fractions as the sum of unique unit fractions. One hypothesis is that the common procedure for dividing (ex. splitting 2 loaves of bread equally among 5 men) made these sums natural and obvious to Egyptians. We’ll discuss this in more detail in the next article of the series.

Division

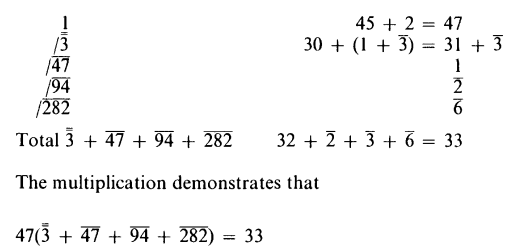

Alright, I’m running out of steam here, so let’s wrap this up. Division was a mess. I am, once again, going to pull an example straight out of Gay Robins’ The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. To divide 47 by 33, the Egyptians would, in their own words, “treat 33 so as to obtain 47.” For example, they might simply observe that

\[47 = 1*33 + \frac{1}{3}*33 + \frac{1}{11}*33 \implies\] \[47 = (1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{11})33 \implies\] \[\frac{47}{33} = 1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{11}\]In this case, we obviously got very lucky with our divisors of 33, so the solution was “easy.” If we instead divide 33 by 47, things get nasty. The Egyptians would again break 47 into a convenient sum and just go to town:

|

|---|

| Dividing 33 by 47 like an Egyptian7 |

Note that the 3 with a double bar above it represents $\frac{2}{3}$. Although $\frac{2}{3}$ isn’t a unit fraction, it apparently didn’t bother the Egyptians, and they frequently included it in their sums.

Conclusion

So now you’ve got the basic idea of how Egyptian arithmetic was performed. With the “how” out of the way, you are free to consider the “why?”. Why did the Egyptians prefer sums of nonrepeating unit fractions? Why did they use powers of 2 when multiplying? I dunno.

Egyptian mathematics is one of the first well-documented mathematical cultures in human history. We take for granted our sleek mathematical concepts and notations, and we often consider our ways to be obvious or “natural.” Effective, unambiguous fraction notation didn’t pop up until at least 500AD, thousands of years after the beginning of written math.7 These things are apparently not intuitive until after the fact. Perhaps we should treat the fundamentals of modern mathematics with a little more respect, or perhaps with a little more skepticism…