Timescales in the Brain and Hierarchical Reasoning Models

- Hierarchical reasoning models: Very cool

- What is Autocorrelation?

- How does autocorrelation relate to neuroscience?

- Anything else?

- Conclusion and what’s next

Hierarchical reasoning models: Very cool

Recently there has been discussion about a new ML architecture, hierarchical reasoning models. Although it’s too soon to say whether they’ll take off, I thought the paper seemed pretty interesting. I noticed the authors made an effort to ground their ideas in cognitive science and neuroscience. One particular comment stood out to me:

The human brain provides a compelling blueprint for achieving the effective computational depth that contemporary artificial models lack. It organizes computation hierarchically across cortical regions operating at different timescales, enabling deep, multi-stage reasoning. Recurrent feedback loops iteratively refine internal representations, allowing slow, higher-level areas to guide, and fast, lower-level circuits to execute—subordinate processing while preserving global coherence. Notably, the brain achieves such depth without incurring the prohibitive credit assignment costs that typically hamper recurrent networks from backpropagation through time.

This was news to me. When did we figure all this out about the brain? I started clicking through citations and got mired in some shenanigans, but I think I’ve mostly figured it out now.

I’ll probably write more about hierarchical reasoning models in the future, but I think this subject alone makes for a relatively interesting article.

We’ll start by defining autocorrelation, which will be the lynchpin for the empirical experiments that identified this hierarchy of timescales in the brain.

What is Autocorrelation?

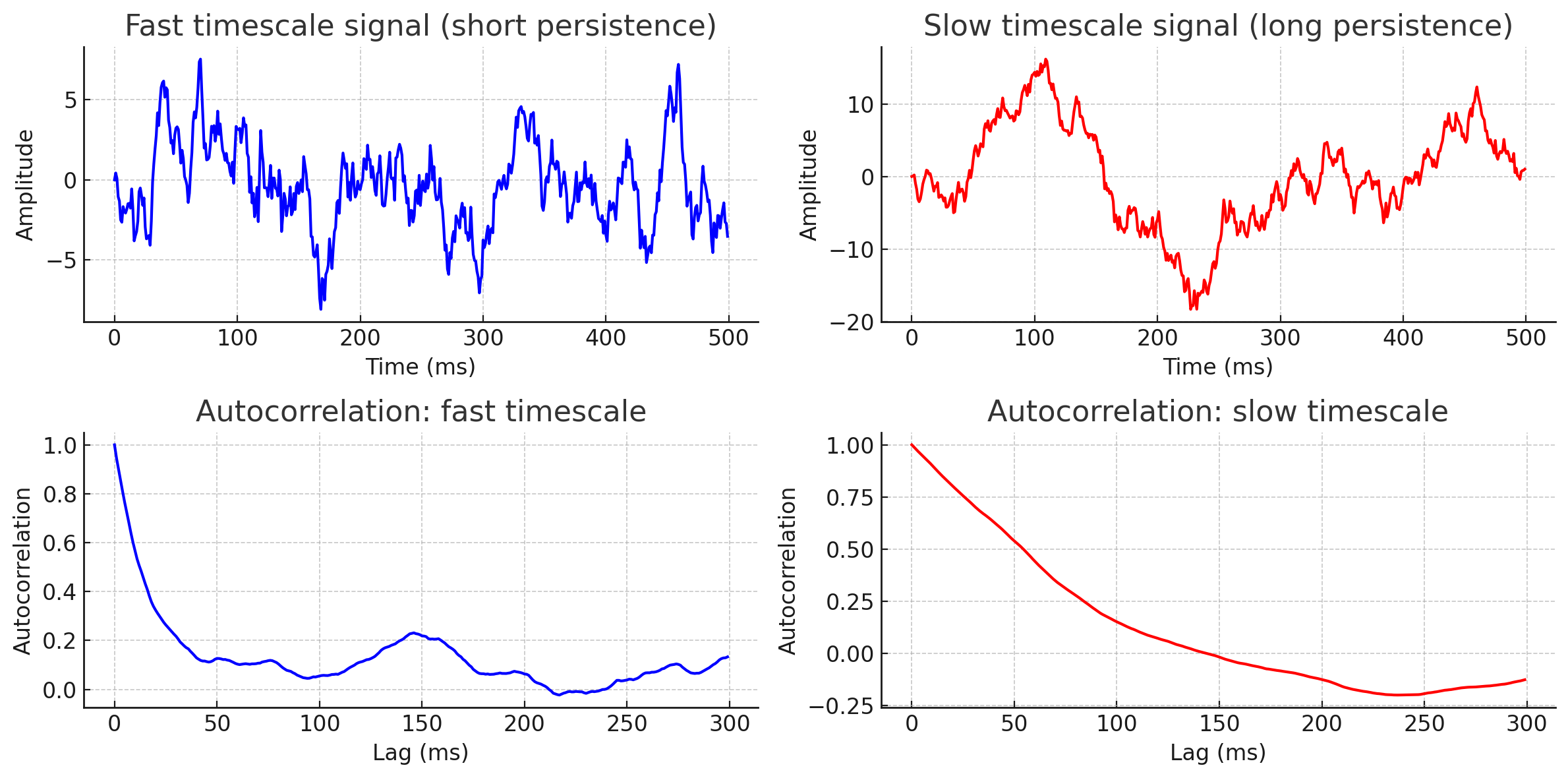

Let ${X_t}$ be a real-valued random process where $X_t$ is the realized value at $t$ for a given run. Supposing we have mean $\mu_t$ at time $t$ and variance $\sigma_t^2$ at each time $t$, then the autocorrelation function is defined by

\[R_{XX}(t_1,t_2)=E[X_{t_1}X_{t_2}]\]So if the process tends to be similar at two times, the autocorrelation of those times will be positive-valued. If the process tends to have opposite signs at two times, the autocorrelation will be negative-valued. Autocorrelation near zero indicates the two times are not correlated at all.

tau_fast = 20 # ms

noise_fast = np.random.randn(len(time))

signal_fast = np.zeros(len(time))

for t in range(1, len(time)):

signal_fast[t] = signal_fast[t-1]*np.exp(-dt/tau_fast) + noise_fast[t]

tau_slow = 200 # ms

noise_slow = np.random.randn(len(time))

signal_slow = np.zeros(len(time))

for t in range(1, len(time)):

signal_slow[t] = signal_slow[t-1]*np.exp(-dt/tau_slow) + noise_slow[t]

If you have a discrete signal $x[n]$, with $n = 0,1,\ldots,N−1$, the sample autocorrelation is:

\[R_{xx}[k] = \frac{1}{N-k} \sum_{n=0}^{N-k-1} \; x[n] \, x[n+k]\]for lag $k = 0, 1, \ldots, N-1$. This definition makes it a little more tangible and easier to visualize.

Autocorrelation shows us how information leaks from our function at different timescales. If the autocorrelation is near 0, the two times share very little information.

How does autocorrelation relate to neuroscience?

Observable timescales in the brain

As early as 2008, very interesting arguments were being made that the brain operates at many timescales. This paper was motivated by mathematical simulations involving bird songs, but the core argument was that a hierarchical modeling of the world allows for processing to occur at several timescales and that this hierarchy of timescales is probably organized in the brain according to distance from primary sensory areas.

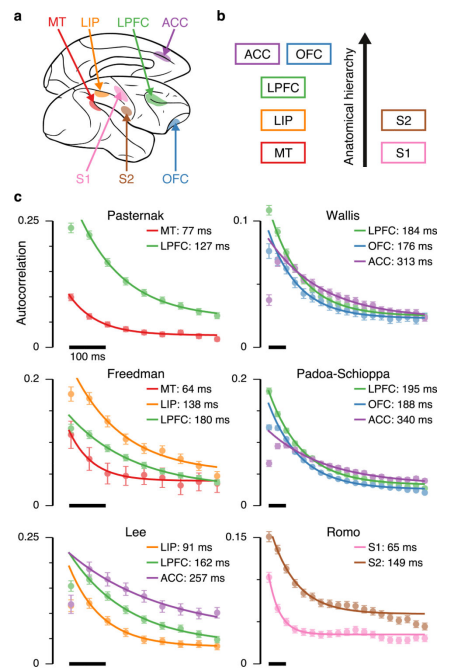

In 2014, JD Murray et al counted neuron spikes over time in various regions of the brain. They found distinct autocorrelations for each region. This indicates that different regions of the brain may be tailored to operate at particular timescales. For example, some regions may be specialized in processing 60ms chunks of audio, while another region might process 300ms chunks. The data seemed to align with earlier hypotheses that timescale would correlate to distance from primary sensory areas.

This blew my mind, btw. I wasn’t aware that we had made this kind of progress in understanding the brain. The idea feels so simple and agreeable, and it’s so satisfying to see clear empirical evidence of it.

But the autocorrelation stuff shouldn’t be be completely clear to you yet. Qualitatively, the graphcs make it obvious that the information decays at different rates for each brain region, but how do you extract a specific number that represents each region’s timescale? There are some additional hypotheses at work.

Deep dive on autocorrelations of neuron spike counts

Recall that the functions of interest are binned neuron spike counts in some brain region. So, for example, they might use 5ms bins and count all the activations that occurred between each 5ms time step. What would you expect the autocorrelation to look like? We can actually make some predictions using knowledge about neurons.

The nuance of the brain’s mechanics are largely unsolved, but we do understand certain base behaviors in the brain. For example, we have a decent understanding of individual neurons. It’s common to model neurons as leaky integrators.

\[dx/dt = -Ax+C(t)\]Where $C(t)$ is the input and $A$ is the rate of leakage. Note that without the first term, we’d have $dx/dt=C(t)$, and thus $x(t)$ would just be the integral of our input function. but the $-Ax$ term contributes a reversion towards 0 over time which erases old information.

For neurons, the input would be the sum of all the neighboring neurons. Obviously, this system is too complex to model in depth, but we can take a toy model and make some observations. For example, what if the input was just random noise?

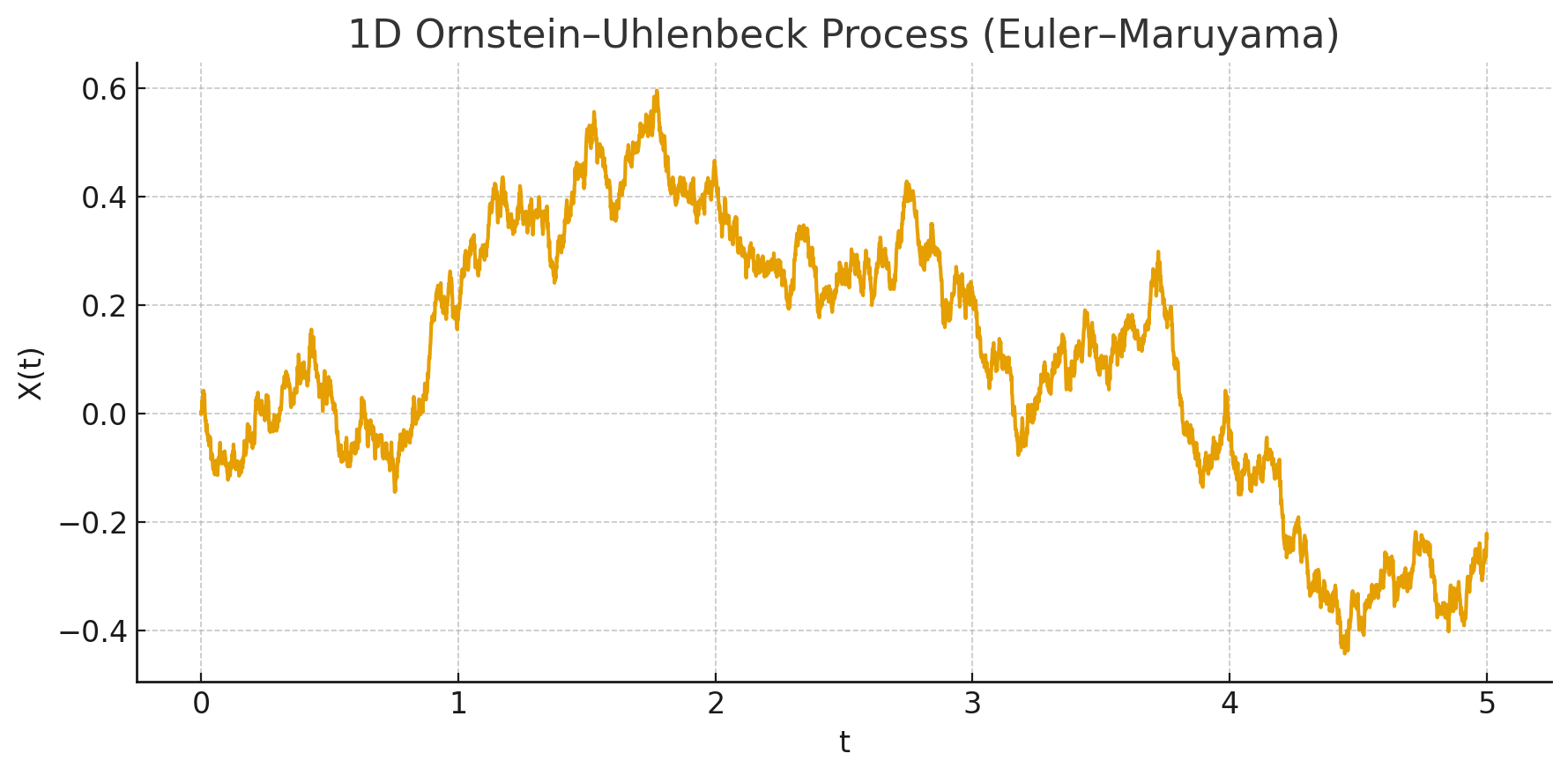

A leaky integrator whose input is essentially just Gaussian noise is actually well-studied model called the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process and can be modeled using the stochastic differential equation

\[dx_t = -\theta x_t dt + \sigma dW_t\]where $\theta > 0$ and $\sigma > 0$ are parameters and $W_t$ denotes the Weiner process. Basically, you’ve got some random Gaussian stimulus and a tendency to revert to 0.

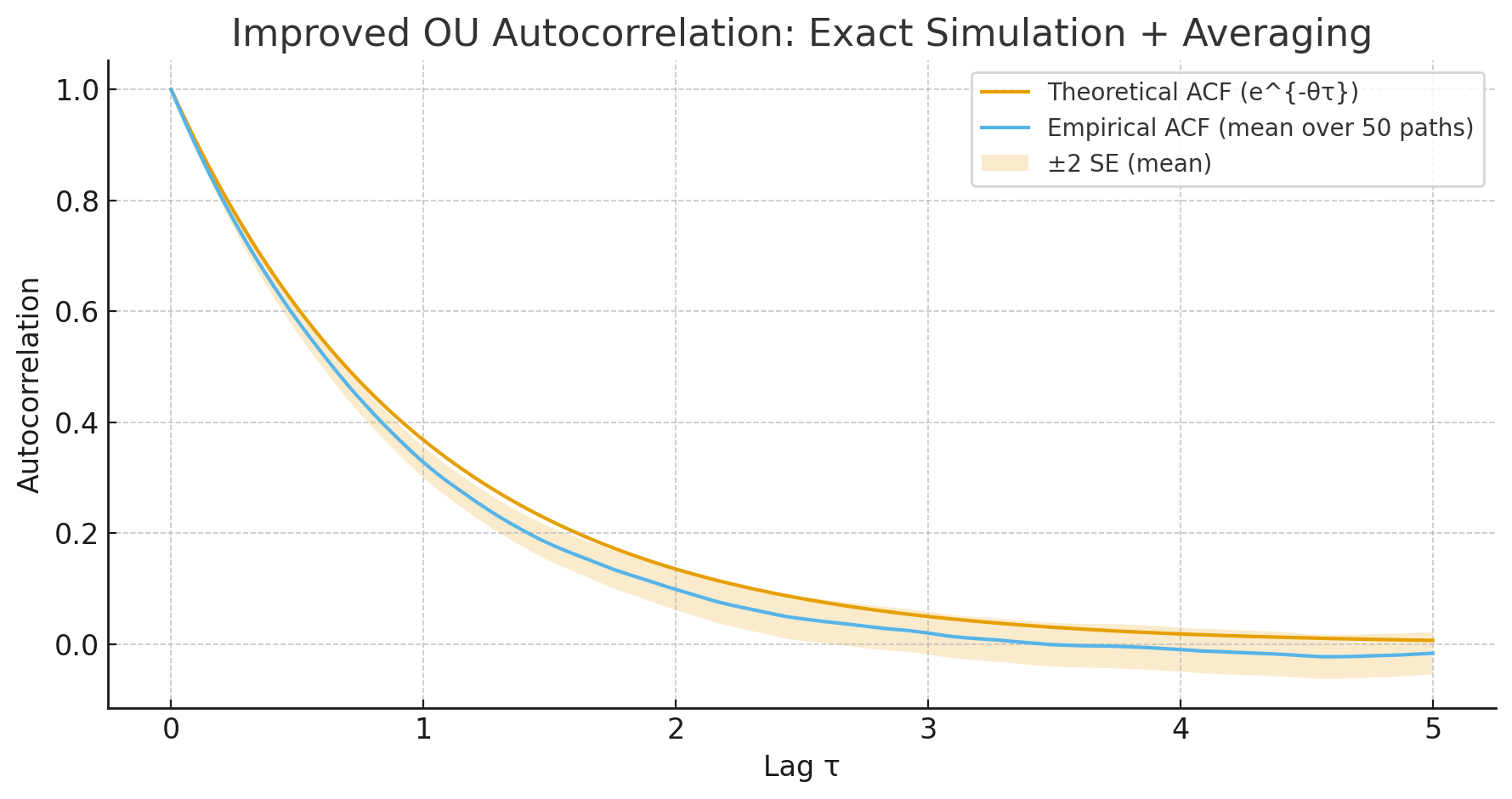

An interesting property of Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes is that the autocorrelation is an exponential. (Note: Woah! Ito calculus!)

My understanding is that researchers similarly assume neurons will act like leaky integrators in a noisy environment, and thus the autocorrelation of neuron spike counts will be exponential. For example, Murray’s 2014 paper regressed on the autocorrelation data using

\[R(k\Delta)=A[\exp(-\frac{k\Delta}{\tau})+B]\]where $k\Delta$ is the lag time in ms and $\tau$ is called the intrinsic timescale of the region. Regression determines $A$, $B$, and $\tau$. Mathematically, when $k\Delta = \tau$, the exponential will have decayed to about 37% of its maximum contribution, which is why $\tau$ serves as a nice indicator of the general timescale of the exponential.

Whatever the motivation for the use of exponentials, they’re commonly used to approximate timescales, they tend to fit the data well, and many papers that use them are highly cited. The academic community seems quite receptive to the idea of timescales in the brain that can be quantified by regressing the autocorrelations of neuron spike counts.

Anything else?

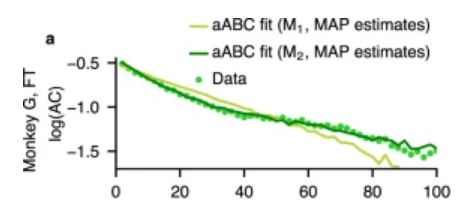

I’m not sure there’s a whole lot more to say about this topic. There is some other interesting research. This new paper suggests that the intrinsic timescales of regions can vary during cognitive tasks or that there can be multiple timescales. In the plot below, you can see the log-linear plot of the autocorrelation of neuron spike counts. Recall that usually the autocorrelation is an exponential, so the log-linear plot would be a straight line.

The authors claim there are actually two regimes here, indicated by the elbow at around 40ms. This indicates that the spike counts have two dominant timescales.

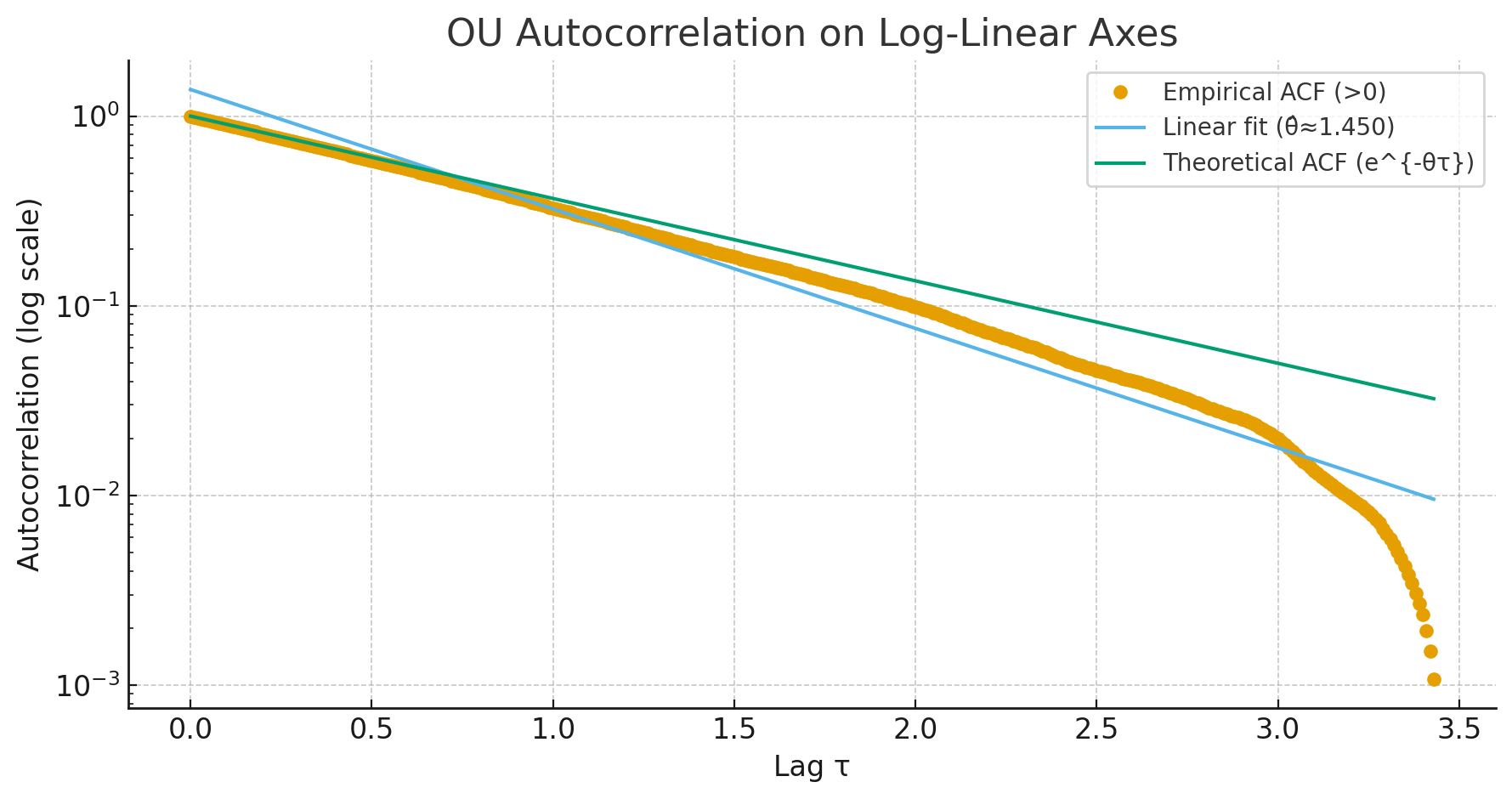

I tried to do a little simulation to see if I could generate data with similar behavior. As a baseline, here’s the autocorrelation for a standard Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process on a log-linear plot:

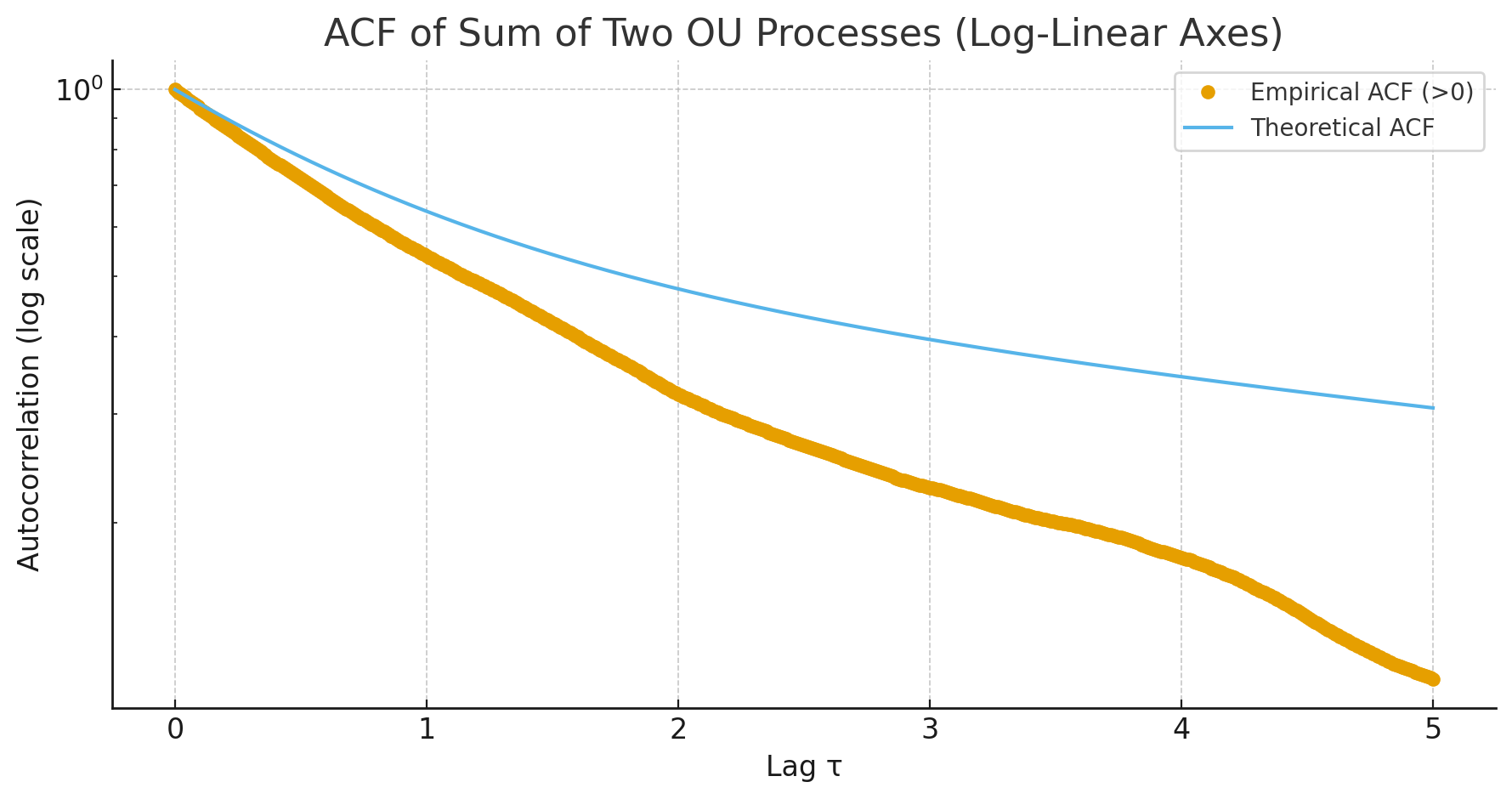

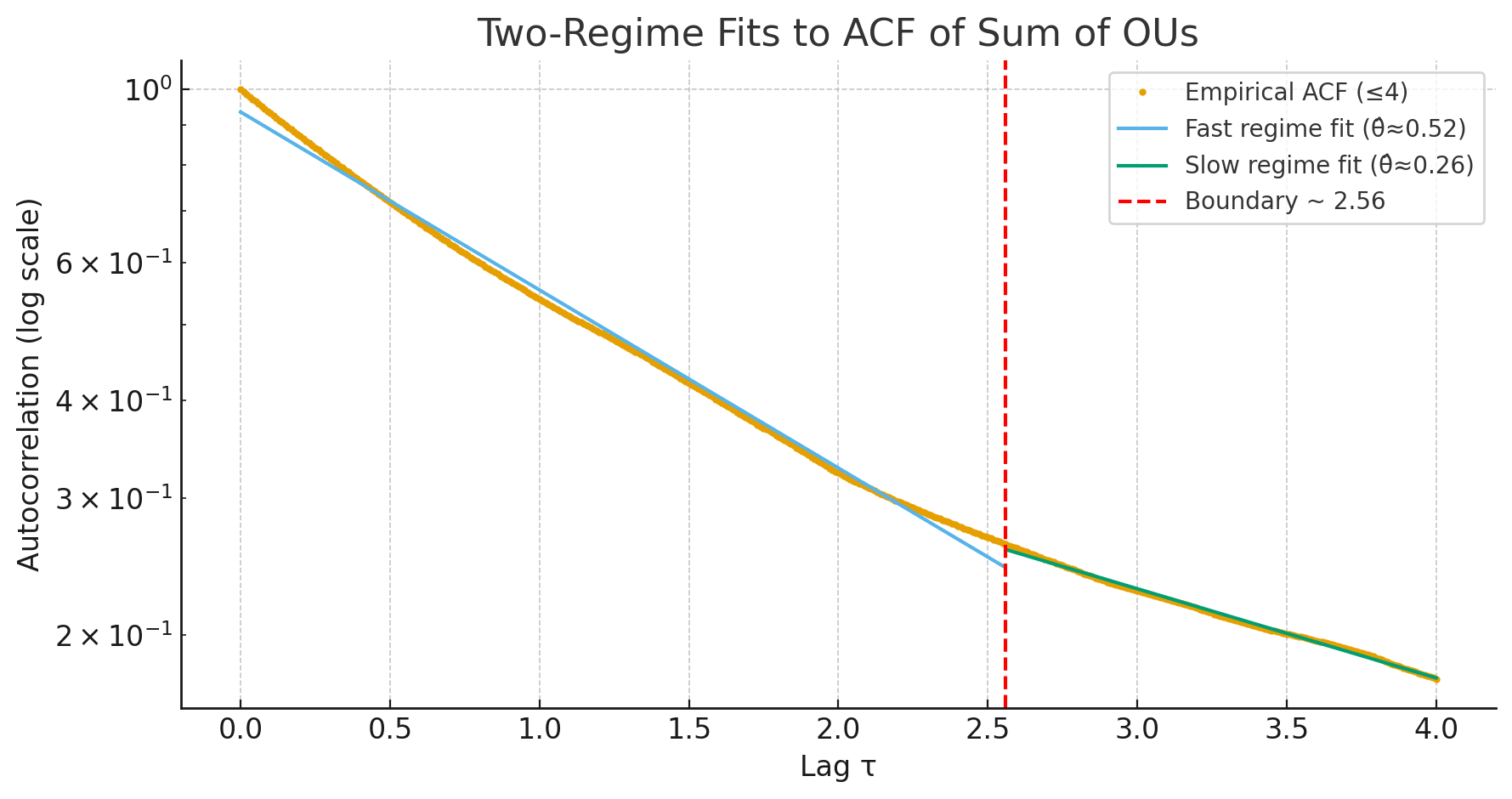

You can see it’s approximately linear (Note: I think the tail falling off is due to the finite data and the way I measure? Not sure…). To get data with two timescales, I summed two OU processes with different timescales. The result looks like this:

And I think the timescale division should be at around 2.0-2.5? Hard to say for sure, but I think I see it.

This is pretty hacky and might not be valid. It’s also irrelevant to hierarchical reasoning models, but it was interesting to see what’s currently being studied in neuroscience.

Conclusion and what’s next

It’s pretty interesting to see what we know about the brain and how we think. There are a few other interesting citations in the HRM paper that I want to investigate. For example, Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought caught my eye.

I’d also like to look at HRMs themselves and see what they’re actually meant to do. If nothing else, it’s a pretty interesting read, and the results thus far have been promising. It will be interesting if someone tries to scale them up.

Another note is that this article was hacked together very quickly after a few days of skimming papers and ruminating. I’m experimenting with a faster composition process motivated by the fact that no one reads my shit anyways. Why should I polish if the vast majority of engagement is only surface level?

If I’m being honest with myself, my articles were only ever intended to be bait that lures interested parties into having discussions with me. I think articles with this level of quality could still serve that purpose. They don’t need to be targeted at a mass audience. On the other hand, I haven’t had a lot of time to play devil’s advocate and be critical of my own thought process, so hopefully there are no more delusions or blatant errors than usual.

Lastly, the math around autocorrelation of OU processes is really interesting. It might be the first time I’ve ever “needed” Ito calculus. That was quite a thrill. I might hang around in this subject matter for a bit.