The Mystery of the Frog Riddle

- Problem Statement: Suppose You Must Lick A Frog

- Plot Twist: Losing My Marbles

- Clarifying the Frog Problem

- The Boy or Girl Paradox

- The Crux

- Conclusion

- PS

Author’s Note:

I have significantly overhauled this article since it was first published. Many readers crafted finely-tuned arguments, precisely identifying the logical weaknesses of my original post.

In response, I have shuffled the logical weaknesses of the article around, rendering all previous discourse nonsensical.

Problem Statement: Suppose You Must Lick A Frog

Recently a friend of mine, Seong, posted an interesting video called “Can you solve the frog riddle? - Derek Abbot” in his Discord server. The video describes a statistical puzzle:

The problem statement is as follows:

…You’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom. To save your life, you need the antidote excreted by a certain species of frog. Unfortunately, only the female of the species produces the antidote, and to make matters worse, the male and female occur in equal numbers and look identical, with no way for you to tell them apart, except that the male has a distinctive croak…

To your left, you’ve spotted a frog on a tree stump, but before you start running to it, you’re startled by the croak of a male frog coming from a clearing in the opposite direction. There, you see two frogs, but you can’t tell which one made the sound… You only have time to go in one direction before you collapse.

What are your chances of survival if you head for the clearing and lick both of the frogs there? What about if you go to the tree stump?

The video eventually gets around to describing the proposed solution:

So here’s the right answer: going for the clearing gives you a two in three chance of survival…

When we first see the two frogs, there are several possible combinations of male and female. If we write out the full list, we have what mathematicians call the sample space…

The sample space for the frogs in the clearing looks like this:

Frog1 | Frog2

-------------

Male | Male

Male | Female

Female| Male

Female| Female

Then,

Out of the four possible combinations, only one has two males… The croak gives us additional information. As soon as we know that one of the frogs is male, that tells us there can’t be a pair of females, which means we can eliminate that possibility from the sample space, leaving us with three possible combinations.

Of them, one still has two males, giving us our two in three chance… of getting a female.

There you have it! It’s all clear, right? We see that probability is mysterious and confusing and you can always solve your problems by appealing to the sample space. There’s nothing left to talk about, case closed, see you later.

Plot Twist: Losing My Marbles

It was late last night. I had just finished watching the frog video, and I was laying in bed feeling quite smug. Then, I received the following messages:

This made me feel bad.

Let’s start with the base case. Suppose you have the bag with just one marble in it. Suppose this marble is equally likely to be red or black. If you were to draw the marble of the bag, it’s a one out of two, i.e. 50%, chance that the marble is black. No mystery there.

Now, let’s take the bag with the unknown marble again. This time, we drop a red marble into the bag and give it a good shake. When we dump both marbles out of the bag, what are the odds we find a black marble? Well, let’s use the sample space approach from the frog video:

Marble1 | Marble2

-----------------

Black | Black

Black | Red

Red | Black

Red | Red

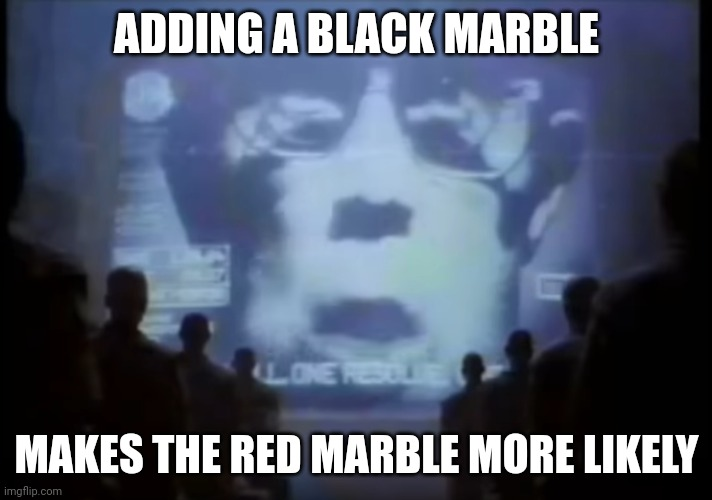

But we know one of the marbles must be red, so Black Black can be crossed off the list. This leaves three possibilities, and two of them involve a black marble, so… There’s a two in three chance of finding a black marble?

To be extremely clear, the conclusion here is this: dropping a red marble in the bag increases the chance that the unknown marble will be black. You can extend this to show that as you add red marbles, the probability of the bag containing a black marble continues to rise.

So what, do we just lay down and take this? Is this the reality we live in?

I think not.

Clarifying the Frog Problem

We are not the first people to feel upset by this video. Additionally, we are not the first people to take a whack at correcting it. The cited attempt fixes the problem by assuming additional information. They assume males have a 50% chance of croaking, and females have a 0% chance of croaking. Then it follows that the probability of finding a female frog in the clearing matches the 2/3 from the original video. Another weird consequence is that the probability of the frog on the stump being female is now also 2/3, so both directions offer the same probability.

I wanted to clarify the original problem so that it could be solved unambiguously, but I also wanted to keep the problem as close to the original formulation as possible.

One way to remove ambiguity from the frog problem is by making it complete from a frequentist perspective. In other words, we should define the problem such that it contains sufficient information to set up and perform repeated trials. Then any mathematical proof about probabilities has a clear meaning: it is a statement about the quantity of each outcome after repeated trials (when the number of trials is very large). This comes with the added bonus that we can verify our theorems empirically.

I found two formulations of the frog problem which are complete from the frequentist perspective. We will discuss both below.

Shared Assumptions

Both formulations use the following assumptions:

- The genders of frogs are independent and identically distributed.

- $p(M)=p(F)=0.5$ for an arbitrarily sampled frog.

- If you go to the stump, you will sample one frog.

Frog Problem Formulation 1

Additional assumptions:

- If you go to the clearing, you will sample one frog and additionally receive a male frog.

- If you go the clearing, there is a 50% chance you will sample before receiving the male frog (and a 50% chance of the converse).

Note that this is equivalent to randomly assigning one of the frogs to be male (50/50 which frog gets chosen) and then randomly sampling the other frog’s gender.

So what can we prove about this formulation?

For the stump, it follows trivially from (2) and (3) that $p(M)=p(F)=0.5$, so you’ve got a 50% chance of getting a female frog.

How about the clearing? Well, using (1), (2), and (4), we see that the frog we will sample has probabilities $p(M)=p(F)=0.5$. So what do our outcomes look like? This is where we must use assumption (5).

- Sample first, Sample is male (MM): $50\%*50\%=25\%$

- Sample first, Sample is female (FM): $50\%*50\%=25\%$

- Sample second, Sample is male (MM): $50\%*50\%=25\%$

- Sample second, Sample is female (MF): $50\%*50\%=25\%$

Now, adding these up, we see that (MM) has a probability of 50% whereas (FM) and (MF) together have a probability of 50%.

Thus, it’s clear that there is only a 50% chance that you will survive if you run to the clearing.

I’ve got the data to back it up:

from random import randint

num_trials = 1000000

num_trials_survived = 0

for i in range(num_trials):

both_frogs = []

known_frog = ['M']

unknown_frog = ['F'] if randint(0,1) else ['M']

# Shuffle the known and unknown frog

if randint(0,1):

both_frogs = known_frog + unknown_frog

else:

both_frogs = unknown_frog + known_frog

if 'F' in both_frogs:

num_trials_survived += 1

print(num_trials_survived/num_trials) # 0.500412

Frog Problem Formulation 2

Additional assumptions:

- If you go to the clearing, you will sample two frogs. If both frogs are female, resample both frogs.

This approach was not intuitive to me. I read a lot of angry Facebook comments describing this method before I finally understood that it was different from Formulation 1.

This approach is computationally annoying because each trial might involve resampling multiple times. (Note to self: is there a way that avoids resampling?) However, it meets all the criteria of the original frog problem, just like Formulation 1.

The single frog on the stump is the same as before: (2) and (3) imply a 50% chance of survival.

The two frogs in the clearing, however, are different. Let’s step through a single trial. For the first sample, there are four possible outcomes:

Sample 1

__________________________________

Outcome | Probability

________________________________

M M | 0.5*0.5 = 0.25

M F | 0.5*0.5 = 0.25

F M | 0.5*0.5 = 0.25

F F (Resample) | 0.5*0.5 = 0.25

If we drew (FF) and needed to resample, the odds would be identical for Sample 2.

So what are the odds that you get (FF) for Sample 1, resample once, and then get (MF) for Sample 2? The answer is $0.25*0.25$. We can similarly calculate the odds of resampling an arbitrary number of times before getting (MM), (MF), or (FM).

It follows that, for each trial, the actual probability for $MM$, $MF$, and $FM$ are all equal:

\[P(MM)=P(MF)=P(FM)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty 0.25^n = \frac{1}{3}\]Then it follows that the probability of survival is equal to $P(MF)+P(FM) = \frac{2}{3}$.

Here’s the empirical evidence for those who lack faith:

from random import randint

num_trials = 1000000

num_trials_survived = 0

def sample_frog():

return ['F'] if randint(0,1) else ['M']

for i in range(num_trials):

both_frogs = sample_frog() + sample_frog()

while both_frogs == ['F', 'F']:

both_frogs = sample_frog() + sample_frog()

if 'F' in both_frogs:

num_trials_survived += 1

print(num_trials_survived/num_trials) # 0.666342

The Boy or Girl Paradox

Let me start by stating a subtle yet crucial mathematical fact:

\[\frac{2}{3}\neq \frac{1}{2}\]We have created two experimental setups which met all of the criteria from the original problem, and each setup produced different probabilities of survival. How? Why? Let’s reiterate what we know:

- Both probabilities were derived incontrovertibly from their respective assumptions

- In both formulations, there are two frogs in the clearing such that at least one frog is male

- The only difference between the two formulations is how we sampled the two frogs in the clearing

It turns out that we have stumbled into the Boy or Girl paradox. The paradox regards a set of two questions which first appeared in 1959 in the Scientific American. The questions were presented as statistics brain teasers. We are most interested in the second question of the two:

Mr. Smith has two children. At least one of them is a boy. What is the probability that both children are boys?

It wasn’t until after publication that the author, Martin Gardner, realized the question was incomplete; the answer could be $\frac{1}{2}$ or $\frac{2}{3}$ depending on how we determined that “at least one of them is a boy.”

According to Wikipedia, the two outcomes can be obtained from the following two sampling procedures:

From all families with two children, one child is selected at random, and the sex of that child is specified to be a boy. This would yield an answer of 1/2.

From all families with two children, at least one of whom is a boy, a family is chosen at random. This would yield the answer of 1/3.

Can we translate this into frog licking? Let’s start with formulating the question:

- The clearing has two frogs. At least one of them croaks (and therefore is male). What is the probability that both frogs are male?

Now the sampling methods:

-

From all clearings with two frogs, one frog is selected at random, and the sex of that frog is specified to be male. This would yield the answer of 1/2.

-

From all clearings with two frogs, at least one of whom is a male, a clearing is chosen at random. This would yield the answer of 1/3.

We can verify these map to the two Frog Problem Formulations above. Frog Problem Formulation 2 corresponds to selecting a clearing at random out of all clearings with two frogs, one of whom is male. This is why we only throw out (MM) samples.

On the other hand, Frog Problem Formulation 1 corresponds to selecting a random frog and observing that it is male.

Clearly, we are caught in a paradox. And now it’s time to resolve the paradox. We have to decide on a sampling method.

The Crux

So here we are. I’ve tipped my hand. You know everything I know. One question remains.

- Suppose that tomorrow I’m out wandering in a clearing. Behind me, I hear a croak. I turn around and see two frogs. What is the probability that at least one of the frogs is female?

In my opinion, because I did not select the clearing specifically to guarantee that it would have at least one male, then it follows that the first sampling method from the previous section is the correct method, and the probability is thus 1/2.

In my opinion, if you disagree with me, then you are a baboon and the game was rigged from the start.

But I’ll be honest. I’m not 100% sure I’ve got the right answer here, much less that there’s a correct answer at all. But I have to follow my heart, and my heart is telling me that you’re an simpleton if you think the probability is 1/3.

Conclusion

It seems pretty fucking clear to me that this video sucks. At best, it leaves out essential assumptions. At worst, it’s straight-up wrong. I stayed up until 2AM thinking about this, and I almost gave in to the belief that adding black marbles to the bag makes the red marble more likely. This video made me hit rock bottom.

PS

There are other famous problems where different sampling procedures produce different results, such as the Bertrand paradox. The Bertrand paradox is still considered unresolved.

Also, the Marble paradox is left as an exercise to the reader.