How did we think about math before algebra existed?

- Introduction

- Multiplication was a geometrical process

- Euclid’s compass and straightedge constructions (~300BC)

- Appolonius and conics (~200 BC)

- Solving quadratics before vs after algebra, and higher order curves

- Conclusion: Who gives a shit?

Introduction

I tend to view (western) math as being broken up into broad time periods:

- 300BC to 1600: Geometrical intuition

- 1600 to late 1800s: Transitionary period, everyone uses algebra but thinks geometrically

- 1900s onward: Rise of algebra and abstraction

This probably isn’t true, but it reflects some aspects of the truth. The way math was performed until Descartes formulated algebra was insane. I still can’t totally wrap my head around it. Here are some random examples of old math.

Multiplication was a geometrical process

Modern algebraic notation was first formulated by Descartes in The Geometry in 1637. Here’s how he introduces the multiplication everyone was familiar with at the time:

Taking one line which I shall call unity in order to relate it as closely as possible to numbers, and which can in general be chosen arbitrarily, and having given two other lines, to find a fourth line which shall be to one of the given lines as to the other is to unity (which is the same as multiplication)…

- Descartes, The Geometry

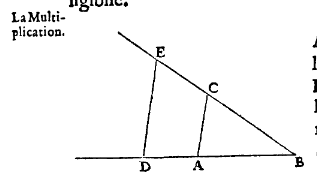

This process is illustrated in The Geometry as follows:

And here’s how Descartes reduced it to an algebraic process:

To [multiply] the lines BD and GH, I call one a and the other b,… then ab will indicate that a is multiplied by b.

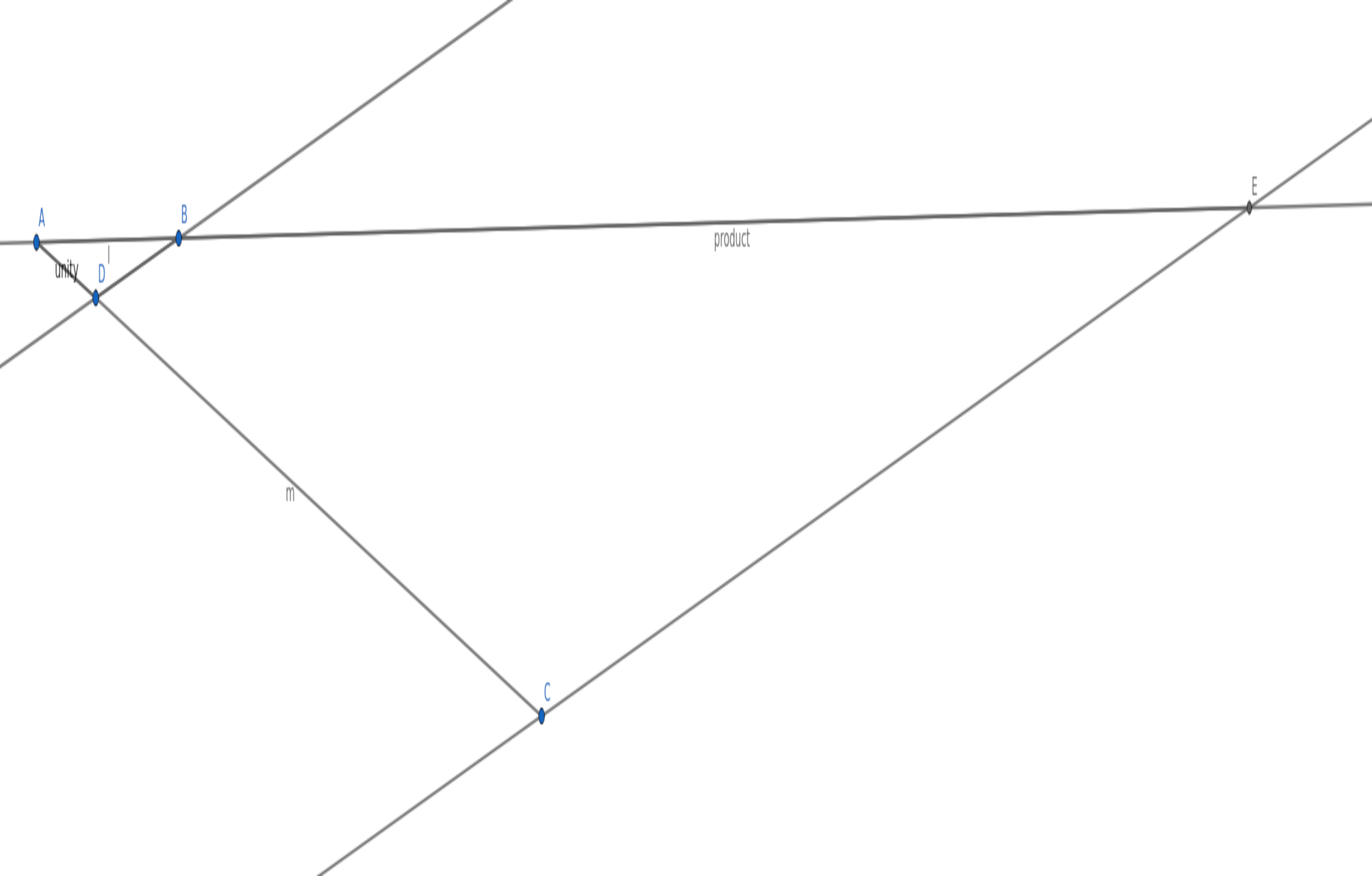

You can find a more modern version of Descartes’s geometric instructions here and, if you’re feeling adventurous, you can try it yourself using Geogebra. Here’s my construction following the modern version:

Where AE is the product of AC and AB with AD being unity. You can verify this by measuring distances with the distance tool to see that:

(AC/AD)*(AB/AD) = (AE/AD)

I had to turn up the number of decimals to display in the Geobra settings to get exactly correct results.

Why does it work? The secret sauce is in similar triangles ABD and ACE. then 1 is to AC as AB is to AE, so 1/AC = AB/AE and thus AE = AB*AC.

This was what we were able to leave behind by adopting an algebraic approach to arithmetic. Multiplication became a numerical process, which is easier to do on the fly and to communicate to others.

Euclid’s compass and straightedge constructions (~300BC)

I won’t go into this in detail because it’s relatively accessible and the material is available online. Basically, Euclid’s studies were all done with a compass and straightedge. Even his studies regarding divisibility and factorization of integers were performed using line segments composed of copies of a special unit-length line segment (check out the definitions in book 7 of Elements).

You can get a summary of Euclid’s Elements on Wikipedia or skim a modern English translation with nice visualizations here.

Some other topics Euler explored with a compass and straightedge:

- Constructing shapes like n-gons

- Inscribing shapes within other shapes

- Constructing similar figures

- Proportions of lines

- Divisiblity and number theory

- Properties of three-dimensional figures like cones, pyramids, cylinders, and spheres

Appolonius and conics (~200 BC)

Appolonius’s major surviving text is named Conics (Some of the translated text available here). Some of the major themes of the text include:

- Constructing ellipses, parabola, and hyperbola as slices of conics

- Calculating tangent lines

- Constructing ellipses, parabola, and hyperbola as loci

Something I found interesting was that the translation had few or no pictures/diagrams. This might be in part because drawing three-dimensional illustrations required the mathematics of projection, which wouldn’t be thoroughly developed for over 1000 years.

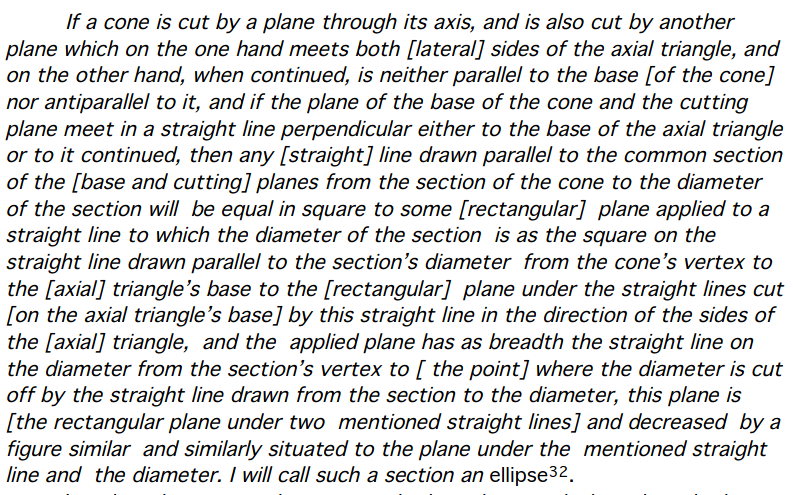

As a result, you get these interesting geometrical arguments which were apparently just imagined rather than physically performed. Here’s how Appolonius defines an ellipse as a section of a conic:

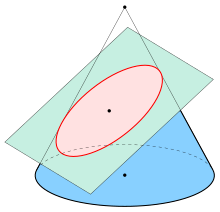

Here’s a modern diagram from Wikipedia representing the same concept, where the red shape is what Appolonius was defining.

I wonder whether Appolonius tried to draw conics and ellipses, or whether it was purely visualization. Or, perhaps even crazier, maybe he could write complex coherent geometrical statements without needing to visualize the particulars at all. Maybe he had no idea what an ellipse looked like.

Although a quick google shows that there were some limited applications of conic sections at the time, so Appolonius had almost certainly seen an ellipse in real life before.

Solving quadratics before vs after algebra, and higher order curves

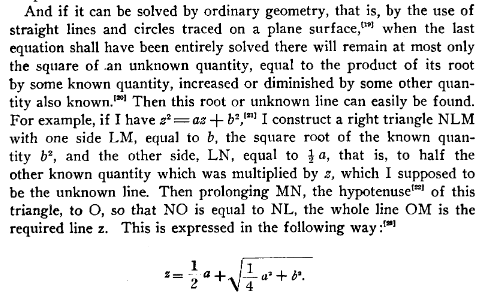

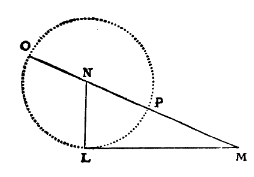

Descartes’s Geometry has lots of cool demonstrations of how algebra simplifies the communication of geometrical problems. One example he gives early on is the solution of a quadratic:

With the accompanying diagram:

Things get pretty crazy after this. At the start of book 2, Descartes rails on the Greeks for failing to analyze any curves more complex than conics. He demonstrates a simple physical contraption which generates curves of a higher order. These curves would be difficult to analyze using the traditional tools of geometry. Then he bangs out the equations and gloats at having easily developed an exact and precise method for analyzing curves which the Greeks never dared to touch.

Descartes claims that, provided there exists a “geometrical” process for constructing a curve, then there exists an equation for the curve which describes all of its properties and allows for analysis of the curve. This also allows us to easily equate geometric problems; two very different geometrical constructions may yield identical equations.

Conclusion: Who gives a shit?

I spend so much time wondering how others “see” math. Something I enjoy about math is coming back to the same old topics and finding that they’ve changed. My understanding of any particular concept is never really complete. Concepts can always be recontextualized in ways that may reveal new lines of questioning.

I wonder whether the development of math was predisposed to happen as it did. There is certainly something to be said about numeral systems and geometric proofs which occurred independently across several cultures in the BCs. Even concepts like the method of exhaustion were separately invented in both China and Greece.

I also wonder what we stand to lose by not studying the history of mathematics. Most math enthusiasts can assign names to mathematical concepts, i.e. “Descartes invented Cartesian coordinates” or “Newton invented calculus,” but learning math today doesn’t make it clear what mathematics was really like in those times, and shit, math was very different.

If we don’t understand the variety of ways that mathematics can be represented, much less the historical development of its representation, then we might miss out on insights that could allow us to improve the clarity and accessibility of mathematics. This is something I worry about. What if I’m doing it wrong? What if we’re all doing it wrong? When I study math, I’m constantly haunted by the thought, “surely this could be easier?”

Not to be a downer. I enjoy the process of discovery, and I’m not upset with the state of modern mathematics. I suppose I’m just optimistic that there are leaps and bounds yet to be made in making math more intuitive and accessible.