Newton’s Law of Cooling

The Birth of the Cool

Newton’s law of cooling is a fun little equation that tells you how fast hot things cool off.

According to Wikipedia, the law can be stated as

The rate of heat loss of a body is directly proportional to the difference in the temperatures between the body and its environment.

Wikipedia briefly attributes the equation to Newton, but when I went to look at Newton’s paper myself, I was a little confused. Then I found some supplementary papers which assured me that I had a right to be confused.

So anyways, here’s a quick little story about the origin of the cooling law.

Newton’s Law of Cooling

Newton’s law of cooling is usually ascribed to an anonymous work (by Newton) published in 1701, Scala Graduum Caloris, or, in English, A Scale Of The Degrees Of Heat.

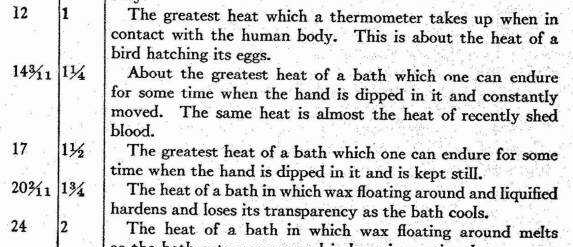

The paper itself has no equations, and in fact the bulk of the paper is just a fat table containing temperatures of various important things:

|

|---|

| Newton deemed these temperatures important and worth measuring |

In fact, the goal of this paper was to create a good temperature scale (Celsius didn’t exist yet) and to observe the temperatures of important events on these scales. No derivations or mathematical finagling.

Towards the end of the paper, Newton also described how he measured the temperature of events hotter than a traditional thermometer can handle, such as the heat at which certain metals stopped glowing. The method involved setting the object of interest on a hot block of iron and timing the iron as it cooled. We’ll discuss how this works at the end of the article, but it relies on the cooling law.

Newton’s profound cooling law–which preceeded a revolution in the science of heat transfer–is actually just an off-handed remark about the cooling of hot iron:

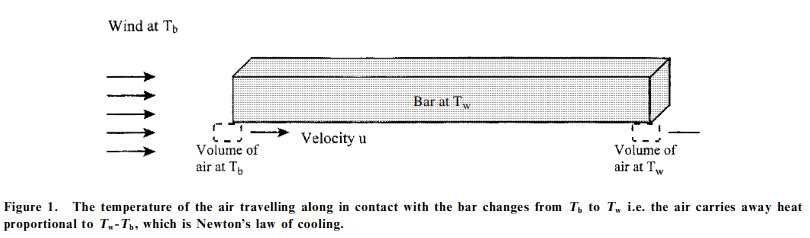

The iron was laid not in a calm air, but in a wind that blew uniformly upon it, that the air heated by the iron might be always carried off by the wind and the cold air succeed it alternately; for thus equal parts of air were heated in equal times, and received a degree of heat proportional to the heat of the iron

The idea can be illustrated quite nicely:

|

|---|

| How air cools iron |

So Newton’s logic was essentially “Heat is very similar to temperature, so if the temperature change is $T_w - T_b$, then the heat exchanged is probably proportional.”

Totally unrigorous, and yet, he pretty much nailed it.

At the time, there was almost no theoretical understanding of heat. The thermometer had only been invented in the last 100 years, and Daniel Bernoulli’s model of heat as particles bumping around was still 40 years from being invented.

This is all to say that “temperature” and “heat” were both super vague terms, and Newton used them interchangeably.

In more modern terms, if we let $T$ be the temperature of our iron and $T_a$ be our ambient temperature, Newton was saying that

\[\frac{dT}{dt} \propto -(T - T_a)\]And he really believed it was an obvious and logical law.

An important consequence noted by Newton is that

if the times of cooling are taken equal, the heats will be in a geometrical progression and consequently can easily be found with a table of logarithms

This means that if $\frac{dT}{dt} = -K(T - T_a)$ for some constant $K$, then we can solve this as a separable differential equation,

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{-K(T - T_a)}dT = dt \implies\\ \int_{T(0)}^{T(t)} \frac{1}{-K(T - T_a)}dT = t \implies\\ \frac{1}{-K}\frac{\log(T(t) - T_a)}{\log(T(0) - T_a)} = t \end{align}\]So Newton was saying that you could measure the heat of the iron at a few points in time, solve the constants in this equation, and then extrapolate to find the heat at times that were too hot for a thermometer to measure. Pretty cool!

In Conclusion

No morals to this story. I just thought this was a fun concept and a cool historical oddity. Thanks for reading!

Oh, addendum: a challenge to my readers. Erin asked me an interesting question: if Newton didn’t write the equation, then when did the modern formulation of the cooling law first appear? If you can solve this, I’d be very pleased.