Lagrangians, Diff Geo, and the Isochronous Curve of Leibniz

Introduction

I’ve been working on building intuitions for advanced classical mechanics. I find that there is an unfortunate trade-off at the development of the Lagrangian. On one hand, setting up and solving problems becomes (hypothetically) easier and more streamlined. On the other, the intuition can become obscured.

I decided to work on some of the earliest problems where the old and new systems collided. Many of these were gravity problems along the lines of, “find the curve between two points along which a descending particle has X property.” For example, the brachistochrone is the curve of fastest descent. It’s the red curve depicted here:

The tautochrone (or isochrone) is the curve such that beginning at any point will take the same time to reach the bottom:

We’ll be looking at another problem, called the “isochronous curve of Leibniz.” Note that this is not the isochrone we just mentioned. The isochronous curve of Leibniz is the curve such that the vertical acceleration at any point is constant. Here is a depiction from this source:

So how will we determine this curve? Well, there are two major approaches. The first uses Newtonian mechanics, and the second uses the Lagrangian.

The Newtonian Approach

The Newtonian approach is interesting and insightful, but it’s also special in another way. Particularly, it sucks. It’s terrible. It’s a lot of work. However, the Newtonian approach introduces us to deep mathematics. Differential geometry is, loosely speaking, the study of the inherent properties of smooth curves and surfaces. Classical mechanics problems like this one bring this theoretical field to life.

How to Be Wrong: Forget About Differential Geometry

Laying Incorrect Foundations

I’ll start by describing my first attempt. Although it’s not correct, it’s only slightly wrong, and it’s a good intuitive foundation.

Firstly, I observed the curve can be described as a parameterized function, $\vec{s}(t)=(x(t),y(t))$. In particular, since our particle travels along the curve, we parameterize the curve with the position function of our particle.

The assumption of the problem is that $y(t)=v_y t$, where $v_y$ is a constant. Now to impose more structure on our curve, we’re going to consider the forces which act on our particle.

In my first attempt, I thought this: “gravity is one force, $\vec{F_g}(t)=(0,g)$, and the only other force is the normal force of the curve resisting gravity at the location of the particle.” Typically once all the forces are identified, the equations of motion can be derived using Newton’s laws.

Doesn’t this sound reasonable? Unfortunately, we’re actually missing a force. If you considered a stationary particle sitting at a point on the curve, we would be correct. However, we’re not telling the whole story for a moving particle.

Discovering a Missing Force

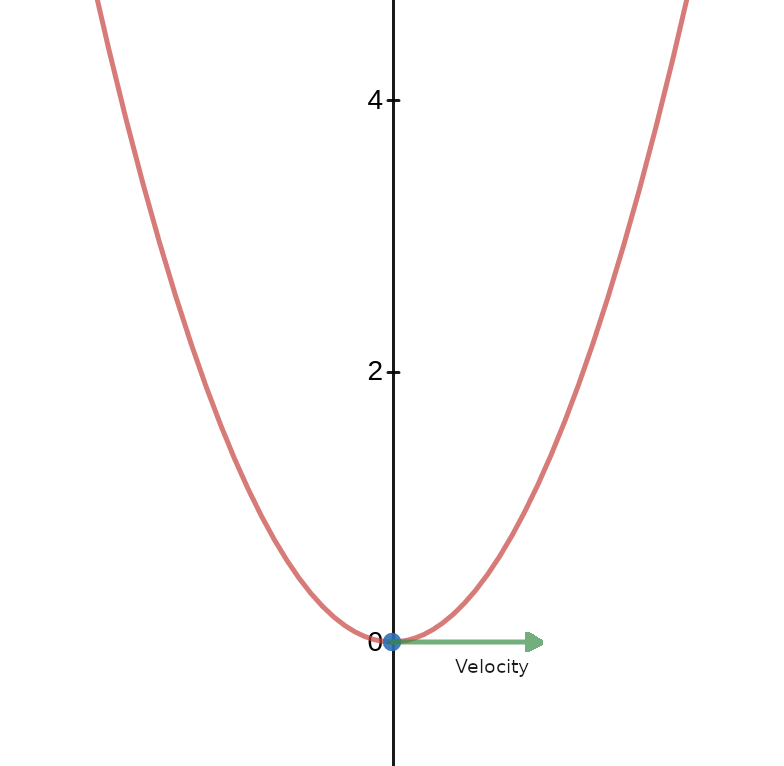

This thought experiment demonstrates that there is another force at play. Suppose we had the curve $s(t)=(t, t^2)$, and a particle on the curve at $t=0$, the bottom of the well. Now let’s spice it up. Suppose that the particle has just come racing down the left side of the curve, and it has velocity $v(t)=(1,0)$. We will also assume that there is no gravity.

Since there’s no gravity, there’s no $\vec{F_g}$ and no corresponding $\vec{F_N}$. But wait… does that mean there are no forces acting on the particle? As you know, $\vec{F}=m\vec{a}$, so that would mean $\vec{a}(t)=(0,0)$. Then the particle would shoot right through the curve!

It seems we have missed a force somewhere in our model. In fact, the curve inherently imparts a force on the particle. How can we describe this force? Well, the force depends on the particle’s position along the curve. Additionally, the force is bigger at “steep” sections of curve.

We also noted this force would inuitively be zero when the particle is stationary, and to add to this, the force will be as big as necessary to redirect faster or slower particles. Thus, the force depends also on velocity.

Now we’ll flesh out this new force more completely and make a correct solution.

A Correct Newtonian Solution

Our previous methodology only needs to be tweaked slightly. The path of our particle is $\vec{r}(t)=(x(t),v_y t)$. There is a gravitational force $\vec{F_g}(t)=(0,g)$ and a corresponding normal force $F_N$. However, we’re now also adding a third force corresponding to the resistance of the curve to the particle.

Let’s get $\vec{F_N}$ out of the way before moving on to this mysterious third force.

From now on, we’ll assume $m=1$ so that I can haphazardly remove it from equations whenever I want.

The Normal Force of Gravity

To calculate the normal force, we’ll have to find the normal vector of the curve at each point. Then, we’ll scale this by $mg\cos{\theta}$, where $\theta$ is the angle between the x-axis and the tangent of the curve.

Our particle has some velocity function, $\vec{v}(t)=(\dot{x}(t), v_y)$. Since the particle travels along the curve, this velocity is necessarily tangent to the curve at every point. As a result, we can use it to calculate a unit normal vector.

Firstly, calculate the unit tangent vector:

\[\frac{\vec{r}'(t)}{\vert \vec{r}'(t) \vert} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2}}(\dot{x}(t), v_y)\]Next, we rotate this counterclockwise 90 degrees to get the unit normal vector. All we have to do is map $(x,y)\rightarrow (-y,x)$ to get:

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2}}(\dot{x}(t), v_y)\]So we now have a unit normal vector. All that remains is to scale it by $mg\cos{\theta}$. How do we calculate $\cos{\theta}$? Well, recall that $\vec{A}\cdot\vec{B}=\vert A \vert \vert B \vert \cos{\theta}$. So we simply dot the unit tangent vector with the unit x-axis vector, $(1,0)$:

\[mg\cos{\theta} = \frac{\vec{r}'(t)}{\vert \vec{r}'(t) \vert}\cdot (1,0) = \frac{-mg\dot{x}(t)}{\sqrt{\dot{x}(t)^2+v_y^2}}\]And thus, finally, we can see that the normal force due to gravity is given by:

\[F_N=(\frac{g\dot{x}(t)v_y}{\dot{x}(t)^2+v_y^2},\frac{-g\dot{x}(t)^2}{\dot{x}(t)^2+v_y^2})\]The Final Force: Repulsion of the Curve

I’m not exactly sure that there’s a satisfying name for this final force. However, we know that it must be related to the velocity of the particle and the curvature of the curve.

The simplest way to approach this problem is by generalizing the methods used on a circle. Consider a point which is bound to a circular path. If the radius of the circle is $r$, and the particle has a tangential speed $v$, then the centripetal force has magnitude $\frac{mv^2}{r}$ and points towards the center of the circle.

For our curve, we can approximate the curvature of a local region around the particle with curvature of a circle of some radius. This circle is called the “osculating circle.” Using the osculating circle, we can deduce the force imposed by the curvature using our simple centripetal force calculations.

But how do we calculate the radius of the circle corresonding to a local region? The direct answer is that the radius is given by

\[\rho = \vert \frac{(\dot{x}(t)^2 + \dot{y}(t)^2)^{3/2}}{\dot{x}(t)\ddot{y}(t)-\dot{y}(t)\ddot{x}(t)} \vert\]But why is this true? Why does it work? Well, firstly keep in mind that in physics, systems are determined by $F=ma$, meaning there’s not usually a need to go beyond two derivatives. Thus, we want a circle that agrees with our curve in its zeroth, first, and second derivatives.

We’ll avoid too many details, but the derivation takes the general parameterized circle and tries to set all the first and second derivatives at a point equal to the derivatives of our curve at a point. Algebraically solving the equivalences reduces to an equation for the radius of curvature. You can find more on this topic here.

We’ll solve the previous equation for our physical problem to get:

\[\vert \frac{(\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2)^{3/2}}{-v_y \ddot{x}(t)} \vert\]Thus, our force from curvature, $F_c=\frac{mv^2}{\rho}$, is

\[\vert \frac{-v_y \ddot{x}(t)(\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2)}{(\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2)^{3/2}} \vert\]which reduces to

\[\vert \frac{-v_y \ddot{x}(t)}{(\dot{x}(t)^2 + v_y^2)^{1/2}} \vert\]And we’ve finally got all the forces to solve this system!

Wrapping up Newtonian Solution

So, I’m not going to go over the algebra involved, but when you sum $F_g$,$F_N$, and $F_c$, you can eventually reduce down to a differential equation for $x(t)$:

\[\dot{x}(t)=\frac{gv_y}{\ddot{x}(t)}\]Solving this, you get

\[x(t) = \frac{2}{3}\sqrt{gv_yt^2+c_1}\]Wasn’t that fun? This process was interesting to me, because I had no idea Newtonian mechanics involved such shenanigans as this. It took me quite a while to explain the missing forces involved. This post in particular helped tip me off.

It turns out this solution scratches the surfaces of differential geometry, and the third force is just one instance of a concept called “Frenet formulas.” While the study of these topics is interesting and valuable, there’s no denying that constructing this solution was somewhat unpleasant.

Seeing Newtonian methods in cases like this can really demonstrate just how convenient the Lagrangian alternative is. No more of this obnoxious force hunting. We’ll summarize this method next.

The Lagrangian Method

I’ll admit I took much longer to work through this than I’d like to admit. However, my colleagues more experienced with Lagrangians solved this almost instantly. I’ll keep method somewhat brief, mostly because I’m not totally confident in my understanding.

Method and Solution

Firstly, our system is described by $\vec{s}(t)=(x(t),y(t))$, as before. The Lagrangian of a physical system describes a property which must be minimized or maximized by the path taken. If the property described by the Lagrangian is unique to a single path, we can use the calculus of variations to deduce the path from the Lagrangian.

The Lagrangian in classical mechanics is typically $L=T-U$, where $T$ is kinetic energy of the system and $U$ is potential energy of the system. It’s derived using the constraint of conservation of energy. In our case, $T=\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(t)^2+\dot{y}(t)^2)$ and $U=gy(t)$ (remember we assumed mass is 1). Thus, the typical Lagrangian for a particle under uniform gravity is

\[L_{general}=\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(t)^2+\dot{y}(t)^2) - gy(t)\]Now, this Lagrangian is too general. It actually applies any conservative system with uniform gravity. We need to introduce more constraints on the variables than just conservation of energy. We will mix in our particular assumption that $\dot{y}(t)=v_y$. So firstly, conservation of energy tells us that

\[T+U=E\]Where E is a constant. Plugging in our $T$ and $U$, and letting $E$ be $T(0)+U(0)$, we get

\[\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(t)^2+\dot{y}(t)^2) - gy(t) = \frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(0)^2+\dot{y}(0)^2) - gy(0)\]We introduce our second constraint by substituting $\dot{y}(t)=\dot{y}(0)=v_y$, giving

\[\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(t)^2+v_y^2) - gy(t) = \frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(0)^2+v_y^2) - gy(0)\]Because I’m feeling particularly lazy, let’s assume that $x(0)=y(0)=0$. This is of no serious consequence; we can always shift the origin to make this true. Then we get

\[\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(t)^2+v_y^2) - gy(t) = \frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(0)^2+v_y^2) \implies \frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(t)^2 - gy(t) - \frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(0)^2=0\]Now, there is one more constraint we will be imposing on our problem. We do not have to do this, but we will assume $\dot{x}(0)=0$. This is equivalent to setting $c_1=0$ in our Newtonian solution. Then we get

\[\frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(t)^2 = gy(t)\]This is the additional constraint we will add to the vanilla Lagrangian. After making this substitution, our actual Lagrangian is now

\[L=\frac{1}{2}(\dot{x}(0)^2+\dot{y}(t)^2)\]Let’s tackle the Euler-Lagrange equations with respect to $y$.

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial y} = 0 \quad \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{y}} = \dot{y}(t)\]Thus, our Euler-Lagrange equation is

\[\frac{d}{dt}\dot{y}(t)=0\]We can easily deduce from this that $\dot{y}(t)=c$, which we know to be $\dot{y}(t)=v_y$, and we can integrate again to get $y(t)=v_yt$. Now, we can actually solve the system by plugging this into our constraint:

\[\frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(t)^2 = gy(t) \implies \frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(t)^2 = gv_yt \implies \dot{x}(t)=\sqrt{2gv_yt} \implies x(t)=\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{gv_yt^3}\]And we’re done!

Unanswered Questions on Lagrangian Method

So, there are some problems I encountered with the Lagrangian method. First and foremost, a keen reader may have noticed that we actually didn’t need to use the Euler-Lagrange equation at all. Once we imposed conservation of energy as well as the assumption that $\dot{y}(t)=v_y$, we could have immediately substituted into $\frac{1}{2}\dot{x}(t)^2 = gy(t)$ and solved.

Why were we able to circumvent Lagrangian methods? I haven’t yet answered exactly what causes this, but I suspect it must have to do with the elementary nature of the solution.

My second problem has been resolved after quite a bit of hassle. I had previously formulated the problem in terms of $t, x(t), \dot{x}(t)$ and got an incorrect result.

I then went on to reformulate the Lagrangian in terms of x(t), y(t), and t. In this case, I got the correct answer solving for y(t) and substituting back into conservation of energy for x(t). However, solving x(t) still gave an incorrect result.

The reason these formulations failed was because of my use of $t$ as a parameter. The Lagrangian, and particularly the Euler-Lagrange equations, depend on the principle of least action. The principle of least action is summarized as:

\[\delta \int_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}} L(\mathbf{q}, \dot{\mathbf{q}}, t) d t=0\]It is within this equation that we can identify the problem in my original formulations. Do you see it yet?

The problem was that formulations such as $t, x(t), \dot{x}(t)$ depend on $t$, but the region of integration with respect to t is not fixed. Indeed, we assumed that we would begin at some $(x_1,y_1)$ and finish at some $(x_2, y_2)$, but the time taken between these points is determined by the solution of the Lagrangian, which gives some “chicken and egg” vibes if we were integrating over $t$.

The fact that our start and finish are spatial coordinates should be a strong indicator that the Lagrangian will be integrating over a spatial parameter.

Additionally, solving in situations where the integration region is not fixed can apparently be addressed by more general principles, such as Maupertuis’s principle.

Part of the reason I took so long to solve this was because one of my erroneous methods led me to an Euler-Lagrange equation that reduced to

\[\frac{d}{dt}\dot{y}(t)=0\]Which led me to conlude $

Conclusion: I am an Amateur

I have a lot to learn. I feel like I made great progress on the Newtonian method. I’d like to investigate further on the nature of curvature and get a more rigorous perspective on how the force inherent to a curve is modeled. I’ve heard that one place this can be investigated is Frenet-Serre formulas. I’d also really like to get closure on the Lagrangian method. Why did all my other formulations fail, and why does the Lagrange-Euler equation with respect to $y$ work? I hope to have these answers for you some day.

Anyways, thanks for reading! Peace out!